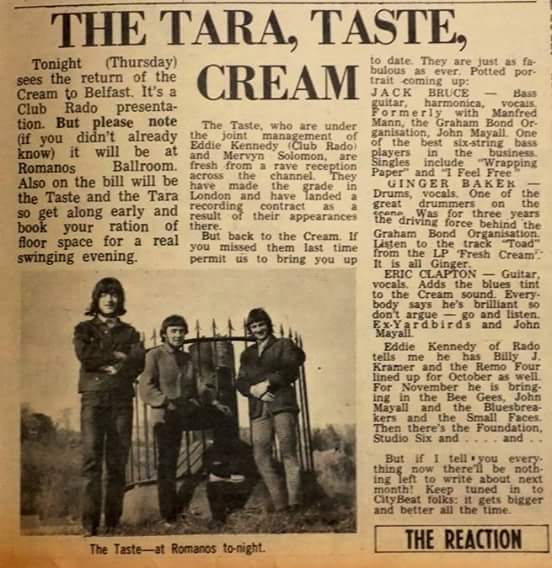

July, 1967, and Taste are settling into their residency at Belfast’s Club Rado in The Maritime Hotel. Already the Cork trio have picked up a loyal local following, and the ballroom is packed with students, sailors, working girls, local bands and music fans from across Northern Ireland. Some are merely curious, wanting to check the hot new ‘southern’ guitar-slinger in town; other are already converts and spreading the gospel that proclaims: “Taste are the best Irish band since Them!” The Rado’s atmosphere is thick with cigarette smoke and excitement as youths pack themselves against the stage, spilling beer as they cheer on the band.

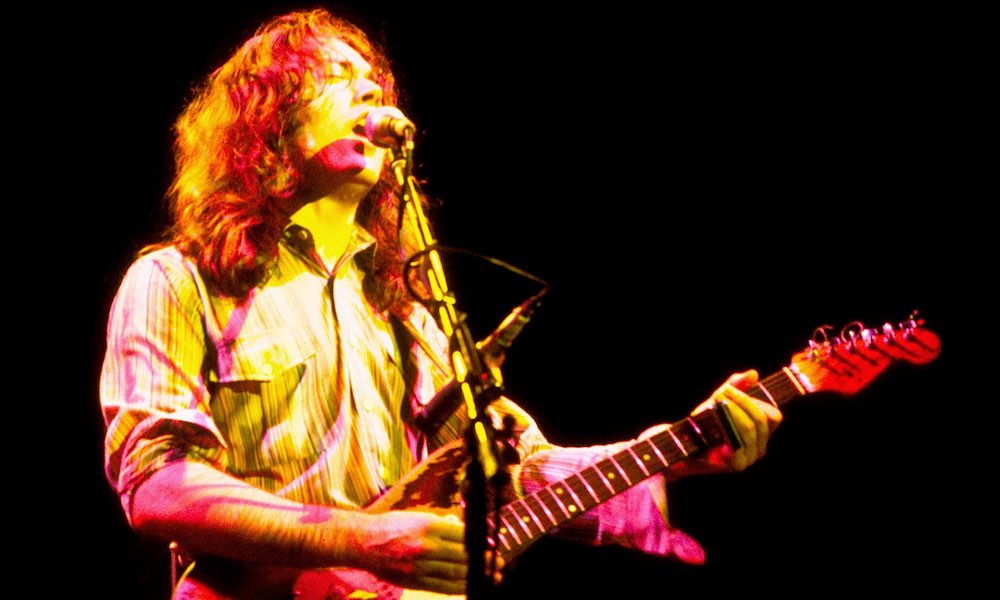

The three teenagers who make up Taste are enjoying themselves immensely. They play a dynamic mixture of blues covers and original songs, sounding raw and dynamic. Their 19-year-old guitarist and vocalist Rory Gallagher blazes up front, his T-shirt soaked in sweat while he caresses great rips of sound from his beloved Fender Stratocaster. Taste slow things for Catfish. Youths punch the air as Gallagher channels feedback into his solo, while sailors whoop with joy and hug the ladies they call “shore relief”.

When “Catfish” finishes, Gallagher announces, “This one’s a new one I just wrote called “Blister On The Moon.” He then plays a stinging riff and sings, ‘Everybody is saying what to do and what to think/and when to ask permission when you feel you want to blink.’ Right now, after years spent in showbands, being told what to play and how to behave, Gallagher is revelling in the freedom of making his music, his way. And Belfast loves him for his freedom and defiance.

Admittedly, not all of Belfast does. Later that evening, after Taste finish their first set, Gallagher steps outside the Rado, wanting some fresh air and quiet. Suddenly, a group of youths surround him, and they aren’t ones he recognises from the venue. “Got a cigarette?” one asks. “Sorry, I don’t smoke,” replies Gallagher. Suddenly he’s set upon. Not for his lack of tobacco, but because his accent gives him away: he’s from the south and on the wrong side of town. Gallagher stumbles, almost falls, but manages to regain his balance as fists and feet rain upon him. He runs for his life and within minutes is inside Club Rado. Everyone notices Gallagher’s terrified expression and battered features. They don’t have to ask what happened. Instead, the Rado faithful empty onto the street, and suddenly the gloating gang are fleeing as music lovers teach the bigots a lesson. An unspoken rule at the Rado involves leaving religion, politics, whatever else, outside. Here Belfast gathers to celebrate the gospel of great blues and jazz and rock’n’roll. And throughout his life, Rory Gallagher always embodied such unity.

If Taste took beautiful shape in Belfast across the summer of 1967 – a summer, locals noted, not marked by love – they would cease to exist in this same city some three and a half years later in the depths of winter. Taste’s final performance took place at Queen’s University, Belfast, on New Year’s Eve, 1970. As the band waited to go on stage for a final time, car bombs exploded across the city. On a wet, windswept, bomb-scarred Belfast night, Taste ended in an atmosphere as bitter as the city’s climate.

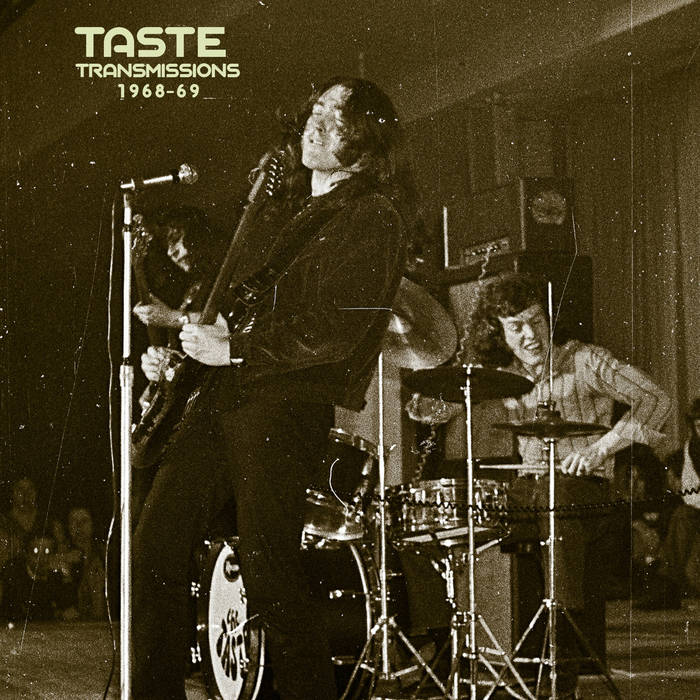

Taste’s brief timeline runs like this: formed in Cork in late 1966, they quickly established themselves in Belfast in 1967, then began to win wider recognition with their regular forays at London’s Marquee. As their UK status rose, manager Eddie Kennedy insisted on changing the band’s rhythm section before they released their eponymous debut album in April 1969. This album achieved immediate continental success.

The band were championed by fellow musicians – the likes of John Lennon and Eric Clapton publicly praised Taste before they even had a record deal – and they played support at Cream’s Royal Albert Hall farewell concerts, as well as touring the US opening for Blind Faith. Their On The Boards album (released January 1st, 1970) won wide critical acclaim and chart success. Taste provided a standout performance at 1970’s Isle Of Wight Festival yet split acrimoniously at the end of that year. Rory Gallagher immediately set off on his solo career while the rhythm section formed Stud, a band as forgettable as their name is vulgar. A flurry of Taste live albums and a collection of 1967 Belfast demos were released across the 1970s, none with Gallagher’s permission or approval.

Those who love Taste’s music must wonder why this band, who shone so brightly and so briefly, appear to have been banished. Gallagher refused to include Taste material in his live sets for the rest of his life: that he felt such enmity towards what he experienced in the band that took him from the showband circuit to international stardom suggests severe trauma. Yet the music contained on Taste’s two studio albums is superb: their eponymous debut is dynamic late-1960s blues rock, while On The Boards is a striking blend of blues, jazz, rock and pastoral psychedelia. Taste were both critically acclaimed and commercially successful, yet in the decades since they split up, their legacy has been marginalised.

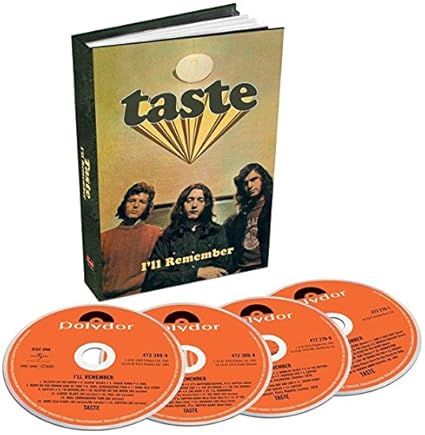

This is finally about to change. A Taste box set, I’ll Remember, is being released alongside a DVD containing the band’s Isle Of Wight performance. These releases are due to the diligence and care of the Gallagher estate, who have worked tirelessly to ensure that Rory’s legacy is properly handled. “For me, Taste has always been a passion,” says Donal Gallagher, Rory’s only sibling, “but this has been a walk through a nettle field.”

on paper, Taste epitomised the Aquarian ideals of the British counterculture. Combining youth and talent, a willingness to experiment and improvise, a dedication to playing for the people and an ability to bring Northern and southern Irish music fans together, Taste embodied the best principles of that era. And Rory Gallagher, in his humility and honest passion, stood for all that’s good in rock’n’roll. But a duplicitous manager would ensure that Taste emerged from the 1960s as burnt and bitter as The Beatles. Perhaps even more so, because few tales of industry machinations are quite as sour as that of Taste.

“Rory was proud of the two albums Taste made,” explains Donal, “but we were never even told by Polydor that they were going to release live Taste albums. And the Belfast demos were never supposed to be issued. The whole situation was a mess and Rory just preferred to avoid dealing with it. We have wanted to see Taste’s recordings handled properly for a long time but my feeling, initially, was that anything to do with Taste becomes a nightmare.”

Donal pauses then adds, “Due to various legalities and personalities involved.”

Nightmare number one was Taste’s manager, the late Eddie Kennedy. Kennedy, a Northern Irish music promoter, caught Taste’s first Belfast performance at Sammy Houston’s Jazz Club. Sensing talent and scenting money, Kennedy signed Taste to both a residency at the Maritime Hotel and a management deal. Seventeen-year-old William Rory Gallagher had gained a musical education way beyond his years in, firstly, The Fontana Showband and then The Impact Showband as they toured Ireland, the UK, Spain and Germany, playing pubs, dance halls and US military bases. Time in London playing the city’s Irish ballrooms had allowed Gallagher to check out that city’s many gifted musicians. He saw Davey Graham in folk clubs and John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers (with Peter Green) in pubs, and it made him determined to lead a stripped-down R&B band. His last showband engagement, at Hamburg’s Big Apple club, found him leading The Impact Showband as a trio. When the Big Apple club’s manager asked where the missing showband members were, Gallagher swore they were all stuck in London with food poisoning. After a week, the manager surmised that he’d been told a fib but Gallagher played with such passion and skill, he let the 16-year-old continue his residency.

Back in Cork, Gallagher retired The Impact Showband and set about forming his ideal band, poaching Norman Damery and Eric Kitteringham from The Axills (Cork’s “answer to The Beatles” at the time). With Dublin being a soul music town, Taste found Belfast more responsive to their blues-drenched sound, and with Eddie Kennedy making promises, the trio settled there in 1967, initially living in the Maritime’s tiny, cell-like rooms (it was built as a residence for sailors between ships).

Van Morrison’s Them had made their name playing at the Maritime Hotel and were now internationally famous, and Kennedy saw in Taste a band who could follow in Them’s footsteps. As Kennedy regularly booked English bands to come and play at the Maritime, Taste mastered their craft opening for the likes of Cream, Fleetwood Mac and Chris Farlowe’s Thunderbirds.

“Those bands would come out to play four or five nights,” says Donal, “and so Taste really got to know them and Rory got to play with a lot of great musicians. The Belfast Taste/Fleetwood Mac gigs were amazing. There was a real purity to both bands and how they played blues. Chris Farlowe had Albert Lee on guitar – he was a brilliant picker right back then! And when Cream came over, Eric [Clapton] was so impressed by Rory that he offered him his Marshall stack to play through. Rory tried it but couldn’t get the sound he wanted so reverted to playing through his Vox amp.”Kennedy’s connections with Robert Stigwood (manager of Cream and the Bee Gees) meant he could get Taste – or The Taste as he initially insisted they were billed – gigs at London’s celebrated Marquee Club. In late 1967, Taste visited London, living out of their van and opening for anyone and everyone. Word spread about the beautifully raw Belfast band and when they returned to settle in London in early 1968, they were soon headlining nights at The Marquee.

“The Marquee was huge back then,” recalls Donal. “This was before they put a bar in so you could pack about 1,500 people in. There was no such thing as health and safety and as it wasn’t licensed, no one ever checked on it. The Marquee was also a place where promoters from across Europe would come to check the new talent.

“After one of Taste’s first London gigs in 1967, this guy from Nottingham, who booked The Boat House, offered us a fiver to come up and support Captain Beefheart. We leapt at it. The fiver probably covered the petrol! I remember we stayed at the worst dosshouse in Nottingham, along with about 30 lorry drivers! But the gig was great and Rory was very impressed by Captain Beefheart and his band as they had strong blues and jazz influences.

“After the show was over, Rory was chatting with Beefheart, and Beefheart said, ‘I hit all the bum notes I can.’ That was new to Rory. He had come up in the showbands where every note had to be perfect. So playing with different bands got Rory thinking about music in different ways.”

Taste then got booked to play at the Woburn Abbey Festival on July 7th, 1968. Woburn Abbey was one of the first British rock festivals and the bill featured the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Donovan. Taste were still unsigned at the time but they produced such a dynamic performance that John Peel, the former pirate radio DJ whose Perfumed Garden show on Radio 1 featured rising stars of the rock underground, told Gallagher that he would make sure Taste got a BBC session. Peel had already begun playing Taste’s debut 45 “Blister On The Moon”. This had been released on Belfast label Major Minor without the band’s consent. The two songs were taken from a demo and it’s likely Eddie Kennedy allowed the single to come out to generate major label interest.

Taste were now rising stars of the British rock scene – John Lennon had attended a Marquee performance and subsequently told a New Musical Express writer: “I heard Taste for the first time the other day and that bloke is going places” – and Polydor expressed interest in signing the band. Kennedy then insisted that the rhythm section be sacked. He told Gallagher that this was at Polydor’s insistence, the label deeming the rhythm section not good enough (listening to the Woburn Abbey concert proves the lie in this). Gallagher said he was having none of this and they would have to find another label. But – and Donal is unsure why – he then backed down, and Damery and Kitteringham were sent back to Cork while Ulster musicians John Wilson and Richard McCracken were drafted in on drums and bass. Wilson-McCracken had recently played in Cheese, a Belfast band Kennedy had managed. The new duo were both gifted, experienced musicians – Wilson had been a member of Them and played on their second album, “Them Again” – and they quickly clicked with Gallagher.

Taste’s new line-up signed with Polydor, with Kennedy promising the band that the label would allow them the kind of independence The Who and Cream were then enjoying. What he didn’t tell them was that as they were minors – the legal age for contracts back then was 21 – it was Kennedy who was signed to Polydor, while the members of Taste were individually under contract to him as employees. Not that the band paid any attention to the intricacies of contracts, preferring to concentrate on taking their music to the people.

“Taste played every gig they could get, every place, building a following,” says Donal who, having started as his brother’s roadie, was now the tour manager. “The crowd would be packed up against the stage and cheering the band on. This was the fuel Rory worked on – Taste would combust on stage, just catch fire with the excitement of the audience and take the music places they didn’t know it could go. I’ve found pictures of them on stage on a winter’s night and they are boiling!”.

Taste settled into two Earls Court bedsits with Rory and Donal sharing one – “two singles beds, a closet, a cooker, a washbasin” – and Wilson and McCracken in the other. The band toured in an old Ford Transit van, playing wherever they were booked.

“Our diary was always quite full because we didn’t mind going up to Inverness one night and Plymouth the next, both for low money,” Gallagher told ZigZag magazine when asked about his early days with Taste. “It was the only way to establish ourselves as far as we were concerned, because people soon forget what they read in a paper but they rarely forget a gig… so we just gradually worked our way up.”

So rooted in playing a highly personal form of blues rock were Taste that Eric Clapton, frustrated by Cream’s inter-member acrimony, insisted they play at the Royal Albert Hall as part of Cream’s farewell concerts. Taste, still without an album out, were thus anointed as Cream’s heirs.

“Cream performed two shows in one evening at the Royal Albert Hall,” recalls Donal, “and that was a pity as it meant everything was rushed. Apparently it was because they could only book the Royal Albert Hall for one night and so they squeezed the two shows in. Also, Tony Palmer was filming the shows and I think he liked the idea of shooting both of them on one day. Yes were also on the bill so for the first show Taste opened, and then for the second show Yes opened.

“To my mind, Taste sounded better on the second show and Rory’s guitar sounded great – he was still playing through his Vox amp. He didn’t use any effects pedals beyond a treble booster to get greater sustain. There were lots of well-known musicians backstage – David Crosby and some of the Bee Gees, among others.”

While the Royal Albert Hall concerts turned the spotlight on Taste, it also brought about a degree of derision: as Cream and Jimi Hendrix had pioneered the power trio format, Taste were dismissed by certain London scenesters as mere Irish copycats.

“Rory had formed Taste in 1966 with no intention of copying anyone,” says Donal. “He was friendly with Jack Bruce, having met him in his Hamburg days, and loved the early Yardbirds – their raw, raunchy blues – but he never aimed for Taste to be like Cream. Obviously Cream had been trailblazers in America so they paved the way for Taste. But if you listen to the Taste albums, they sound nothing like Cream.

“When Cream finally split [following their 1969 US farewell tour], Rory was approached by Eddie Kennedy with the suggestion he join Jack and Ginger [Baker] in a new version of Cream. Eddie was working closely with Robert Stigwood’s agency and it must have been mooted that a version of Cream could continue with Rory in Eric’s place. Rory wouldn’t have a bar of it.”

As Taste’s live reputation continued to grow, Polydor determined to get them into the studio and hired Tony Colton, a highly-touted British singer-songwriter who was, at that time, fronting Heads Hands & Feet as producer. Taste’s self-titled debut album was recorded at De Lane Lea Studios, a facility in the centre of Soho, in one day. The next day was devoted to mixing the album.

Released in April 1969, Taste’s debut album is, essentially, their live show. It opens with Gallagher’s anthem “Blister On The Moon”, He bemoans life spent up and down Britain’s then-primitive motorway network with Dual Carriageway Pain, which is followed by a handful of unremarkable Gallagher originals, “I’m Movin’ On”. This gets played in a remarkably straightforward manner, harking back to Gallagher’s 1950s childhood in Ballyshannon where he was taught the song by his Uncle Jimmy, who returned to Northern Ireland after having worked in Detroit’s car plants.

Taste’s self-titled debut provided a broader showcase for Rory Gallagher, though the guitarist was already well on his way to becoming a national folk hero among his fellow Irishmen. Taste, which arrived on arrived on April 1st, 1969, succeeded on its own terms thanks to stunning heavy rockers like “Blister on the Moon,” “Same Old Story,” and the timeless “Born on the Wrong Side of Time,” as well as a wealth of accomplished blues numbers, both covered (Huddie Ledbetter’s “Leavin’ Blues” and Howlin’ Wolf’s “Sugar Mama”) and original (“Hail,” which particularly highlights Gallagher’s talents; and “Catfish,” where he “out-Gods” Eric Clapton). Before they were done, Taste even found time to visit ‘50s rock via “Dual Carriageway Pain”; and American country music, with an acoustic and slide guitar-infused rendition of Hank Snow’s “I’m Moving On.”

Still, his first sighting alongside the other men in Taste cannot be overlooked, since it stands as Gallagher’s first major step toward immortality as perhaps the ultimate working-class guitar hero.

Taste received largely positive reviews – Gallagher noted that it was “raw and honest” – and sold strongly in northern Europe. The band stayed on the road and went on to break The Marquee’s attendance record (previously held by Jimi Hendrix), but they remained on the same tiny salary Eddie Kennedy paid them. They may have now been internationally celebrated recording artists but they continued to live in grimy Earls Court bedsits.

“Earls Court was dubbed ‘Kangaroo Valley’ back then due to the huge number of Aussies living there,” says Donal. “The bedsit was very cramped and you had to feed the gas meter with an endless supply of coins to be able to cook or get heat. I would always be going off to the local laundry to do the band’s washing – Rory would just sweat through everything on stage – and the lady who owned the bedsit saw me doing this and installed coin-operated washing machines in the basement of our building. In winter, the laundry basement was the warmest room in the building so we would huddle down there, and Rory found it was a place where he could practice guitar and saxophone without annoying the other people living in the building.

“We lived in a crescent and met many other bands living there, including Brian May’s Smile. Brian would come and see Taste all the time. He would hang around after the gig finished to talk guitar with Rory, and Rory would explain to him how he got certain sounds.”

Eric Clapton’s enthusiasm for Taste remained strong and saw that the band were invited to support Blind Faith on their US tour across July and August 1969. While Taste played well, Blind Faith were imploding and, Donal recalls, the tour was poorly organised.

“It had always been a dream of Rory’s to play music in America. But once we got to America, the Blind Faith tour was a shambles. It was very badly managed, chaotic. They didn’t have enough material ready so Eric and Ginger ended up having to do Cream numbers – which is what the audience wanted, but not what Eric and Stevie [Winwood] had formed Blind Faith to do. Everything about that tour was a mess – it really felt cobbled-together – and due to Blind Faith’s controversial album cover [featuring a young topless girl], their record release had been delayed so the audiences weren’t familiar with the new songs. Rory was unhappy with Eddie and disliked playing stadiums, preferring clubs, and animosity was building in the band. Eric worked out something was wrong with Taste and asked me one time: ‘What’s wrong with the guys?’ He could feel the vibes. Rory took on an air of depression on that tour. ”

Taste were well received by US audiences and their debut album on Atco (Atlantic) entered the Billboard and Cashbox charts, but Eddie Kennedy had done little for the band there and, at the tour’s end, they found no further US dates booked. Back in London, Polydor requested that Taste re-enter the studio with Tony Colton to record album number two. This time they were given almost a week to get things done. And Gallagher, emboldened by success and determined to pursue his musical vision, stretched out on what would become known as “On The Boards”.

Gallagher composed all 10 tunes and demonstrated a versatility few could have imagined. Alongside driving blues rockers were acoustic ballads and experimental jazz-blues fusions, with Gallagher playing alto saxophone. No one else in contemporary rock music was creating anything comparable and when “On The Boards” was issued on January 1st, 1970, it entered the charts across Europe and attracted hugely complimentary reviews. Yet when Polydor issued opening track What’s Going On as a single in Germany – it was a Top 5 hit there – Gallagher was furious. Just like Led Zeppelin, he refused to allow singles to be issued from albums.

“I’m not sure where that came from,” says Donal, “as we grew up loving listening to 45s by The Everly Brothers and Chuck Berry. I think Rory saw his albums as akin to what jazz musicians were doing, so didn’t want them chopped up. At that time he had jammed with Larry Coryell and was in awe of Ornette Coleman, so the idea of being a pop star just did not appeal.”

As for Gallagher’s skill on the alto saxophone, which would never feature prominently on his albums again, Donal recalls his brother teaching himself in their bedsit.

“Rory taught himself to play alto sax in one week. He did it in our bedsit in Earls Court. It was a frigging nightmare! He ended up playing into our closet, using it as a sound booth. It got so many complaints from other residents in the building!”

Taste were in the charts and on the road, playing to ever larger audiences, yet remained on the same poverty wages that Kennedy had begun paying them in 1967. “Eddie kept Taste on a meagre weekly salary,” notes Donal. “Rory got an extra fiver a week as he had to buy so many guitar strings. But the band were still playing through the meagre PA Rory had inherited from his showband days and travelling in a very basic Ford Transit with no proper heating. Here Taste were headlining festivals, setting attendance records at The Marquee and topping the charts across Europe, and they were just as poor as when they were an unknown band. It simply wasn’t good enough.”

By the time Taste came to play the Isle Of Wight Festival on August 28th, 1970, the band were on the verge of splitting. Rory and Donal both knew that Kennedy was looting Taste, yet Wilson and McCracken sided with their manager. Just as Noel Redding had resented the attention Jimi Hendrix received, Taste’s rhythm section spoke bitterly of how the focus on the band appeared to be all “Rory, Rory, Rory”.

“Things weren’t looking great for Isle Of Wight,” recalls Donal. “The van was broken into the night before and some of the drum pedals were stolen. This just added to the tension as Rory had been on to Eddie about getting a better van. At the Isle Of Wight, you had a band imploding on itself – Rory was very upset that John and Richard had decided to take the manager’s side. John believed all the promises that Eddie made – how he was going to make them all millionaires and pay a mortgage on John’s house – while Rory felt that Eddie had done what was necessary: he had got them from Belfast to London and had now run his course. And Eddie held on to all the money Taste generated. Also, there was the issue of jealousy: John and Richard resented Rory getting all the limelight but he was the bandleader, the guitarist, the singer, the songwriter.”

Donal sighs wearily as he recalls this difficult time. Taste were a band at the top of their game, widely loved and achieving great things, but they were poor and miserable. “We didn’t even have enough wages to eat properly. It turned out that John and Richard had signed separate contracts with Eddie and that Taste were not signed to Polydor so much as Eddie Kennedy was. All this came to a head two days before the Isle Of Wight. By the time they played the festival, Rory and I knew that Taste were over, that he was going to break up the band and go solo.”

Yet the Isle Of Wight ignited around Taste. Murray Lerner, who was shooting a film of the festival, had planned on only shooting one or two songs of Taste’s set, but they were so exciting and the audience response so strong that he kept the cameras rolling for much of the band’s performance. It’s this footage that features on the Taste Live At The Isle Of Wight DVD.

Gallagher wanted to end Taste after the festival but found out that Polydor had booked a major European tour for the band. Gallagher agreed to do it but insisted that he got paid directly by Polydor. Kennedy continued to treat the band poorly and during this tour, a backstage visitor asked Donal, ‘Where’s the beers? Where’s the food?’ I said, ‘This band don’t get any. What’s it to you?’ He replied, ‘I’m Peter Grant and I manage bands and Taste should be treated better than this.’ We got to talking and Peter would help us get out of Polydor’s clutches – they wanted to hold on to Rory as a solo artist.”

Once the European tour was over, Gallagher made it clear that Taste also were. Gentle as he may have been, he knew he had been robbed by Kennedy and was furious at his bandmates’ disloyalty. He agreed only that the band should play a farewell concert in the city that launched them: Belfast. Finishing on New Year’s Eve appeared suitably symbolic.

“The band performed two shows on the same day,” says Donal. “I guess it was because everyone was trying to earn their last crust. I recall their performance had an eerie feeling to it as they were playing beautifully, playing great music, but very soon it was to be no more. The second concert was at Queen’s University and as it came up to midnight, 11 car bombs had gone off across Belfast. And everyone was saying that the 12th car bomb would go off as it hit midnight. So we were all waiting for this ominous moment.

“In London people were counting down the seconds until Big Ben chimed midnight and in Belfast we were counting them down until the 12th car bomb went off. And you know what? It never exploded. I don’t know if this was due to a fault in the bomb or what, but that is my abiding memory of Taste’s final concert – the band breaking up and Belfast being torn apart by car bombs.”

Gallagher quickly moved on, establishing himself as a hugely successful solo artist. Peter Grant saw off Eddie Kennedy – who initially claimed to “own” the frontman – but Gallagher never saw any of the funds Taste had earned across their four-year existence. As Donal got more involved in managing Rory, he determined to resolve the Taste conundrum.

“I got more and more angry at how he was being ripped off over the Taste material and Eddie was still holding on to some of Rory’s publishing. Then, in the mid-1970s, we had just signed a new contract with Chrysalis and suddenly this album of the Taste Belfast demos came out in the US under Rory’s name and with a photo of him on the cover, as if it was a new album by Rory! I hired lawyers and went after the label and they declared bankruptcy rather than pay up. It cost us a fortune! I then took Eddie Kennedy to court and Rory was very nervous about it. He told me that he doubted he could get in the witness box and testify against Eddie, but Eddie capitulated before it reached court. He then signed over the Taste royalties, although he claimed to have no money so Rory never saw any of the money generated from Taste’s album sales up until then.”

In the early 1990s, the most unlikely of events almost happened: a Taste reunion. “Rory and John Wilson got friendly again after John turned up for a few of Rory’s Belfast concerts. We were considering a Taste reunion being held in Belfast’s Titanic dry dock as part of the Northern Ireland peace process, but then Rory got sick. Anyway, by now we were all talking again and I explained to John and Richard that we had gone after Eddie for the Taste royalties. At around the same time, Polydor announced it was reissuing the Taste albums on CD and I pointed out to them that they did not own the digital rights. We sorted this out and an agreement regarding Taste was finally signed by all parties in 1999. Better late than never.”

Then, in 2000, Wilson and McCracken revived the Taste name (with Sam Davidson doing Gallagher’s guitar and vocals) and went out on the road. If the Gallaghers and the rhythm section had put their differences behind them in the 1990s, this ‘reunion’ again proved divisive.

“It upset me that Richard and John went out on the road again as Taste,” says Donal. “That was an abysmal decision and not in the spirit of the agreement. When I heard about it, I said to them, ‘Why don’t you go out as Stud?’” Donal shakes his head in quiet disbelief, then says, “The synergy of Taste was great. Rory loved playing with the band, the way Richard understood jazz really worked for him. But Taste without Rory… it’s not right.”

What Donal has done is get Taste right. The “I’ll Remember” box set and Live At The Isle Of Wight DVD (“I contacted director Murray Lerner and said, ‘I don’t want my descendants talking to your descendants so let’s get this done’”) capture one of the most remarkable bands of their era. They only existed for a few brief years but the music they created then touched many. And now, treated with the respect Taste deserve, it will continue to do so.

_“I’ll Remember” is out on August 28 via Universal. See http://www.rorygallagher.com for more information.

LESTER BANGS ON TASTE…world’s most famous rock hack was a huge Rory fan

Lester Bangs (1948-1982) was the greatest American rock critic ever to pick up a pen and the only one to be immortalised in a Hollywood film (by Philip Seymour Hoffman in Almost Famous). He was starting out as a freelance writer for Rolling Stone in 1970 when the magazine asked him to review On The Boards. The 21-year-old Bangs gave the album one of his most fulsome reviews ever, noting: “Taste is from the new wave of British blues bands, breaking through the slavish rote of their predecessors into a new form that can only be called progressive blues. In other words, they use black American music as the starting point from which to forge their own songforms and embark on subtle improvisational forays.

“From the first notes of What’s Going On, the tightness and precision of this band’s instrumentalists is evident – the bass always complements the lead perfectly, never resorting to Jack Bruce fidgetings. And the crackling power of the guitar solo is made doubly heady by Rory Gallagher’s unerring sense of restraint… But Taste is evolving into much more than just another heavy voltmeter trio, as It’s Happened Before, It’ll Happen Again makes clear. After two angular, uptempo vocal choruses – like scat singing with words added – Gallagher takes off on a long whirlwind of a solo flight, first on guitar and then alto sax, that is jazz and rock and neither precisely.

“You can hear distant echoes in his guitar solo of Gábor Szabó, Wes Montgomery and probably The Tony Williams Lifetime’s John McLaughlin, but Gallagher has digested his mentors, be they blues bards, jazzmen or The Rolling Stones. He is his own man all the way, even on sax, where his statements are doubly refreshing by their piercing clear tone and the coherence of the ideas – we have needed a rock saxist with the inspiration and facility to blow something besides garbled ‘free’ shit.

“It may seem unfair to concentrate almost exclusively on Gallagher, but the group is really his own vehicle in every way – besides playing lead guitar and sax and harmonica, he also sings lead and wrote all the songs. His voice is crisp and personal and blessedly free of strained mannerisms. Gallagher is no shouter when he doesn’t need to be – he treats his voice just like his other instruments, with an artist’s sense of ease and care for their delicacy…

“It seems a shame to even suggest that Taste be classed in any way with that great puddle of British blues bands. Everybody else is just woodshedding – Taste have arrived.”

![Check Shirt Wizard - Live In '77 [VINYL]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/91pwR95Qz6L._AC_SX679_PJautoripBadge,BottomRight,4,-40_OU11__.jpg)