“Brown Eyed Girl” hit the radio waves 50 years ago. The hit became a landmark moment for its singer, Van Morrison, who had just left his home of the Belfast-born Irish soul troubadour Van Morrison and his band Them to break out on his own. “Brown Eyed Girl” was a start, but it wasn’t what Morrison saw himself doing.

Throughout his career, Morrison has weaved into many genres, but the thread of deep spirituality has bound the pieces together. His perspectives have shifted dramatically — from mystic poeticism to born-again Christianity and everything between, even dabbling in Scientology — but it’s always there, and it’s part of what makes his catalog so fascinating. he has remained a conspicuously remote rock star, with a well-earned reputation as one of the truly difficult and diffident figures in popular music. Tales of his crankiness are legendary, and include hectoring inattentive audiences, abusing fellow musicians both on and off stage,

Van Morrison is one of rock’s greatest poets, and no matter what he’s preaching or what the band’s playing, it’s profound and it’s certainly always got soul.

Astral Weeks

Morrison first came to prominence as a preternaturally gifted teenager fronting the gritty Blues soul act Them. By 1967, he had already composed the now standards “Gloria” and “Brown Eyed Girl,” which remain two of his best-known songs. But the idiosyncratic and complicated Morrison was always a one-man gang at heart, and the inevitable launch of his solo career would bring to bear the intensely sad, sublime and inventive chamber pop of Astral Weeks, an instantly legendary album whose luminous power has only increased with age.

It’s almost impossible to pick one track from the close-stitched tapestry that is Astral Weeks, where every song – excepting, perhaps, the smooth swing of The Way Young Lovers Do makes persuasive claim to being a masterpiece. Morrison’s dreamtime evocation of postwar Belfast was recorded in a handful of hours with some of America’s finest jazz musicians, relying on intuition and alchemy to bring the songs of memory and rebirth to vivid life. Madame George exemplifies the album’s mood of heightened nostalgia, its pitch of ecstatic longing. Earlier attempts at the song recorded with Berns came out sounding boorish and flat-footed. Now working with New York producer Lewis Merenstein, Morrison and his hired hands instinctively divine the heart of it, capturing an entire street world in 10 minutes with three simple acoustic guitar chords, fluttering flute, backstreet violin and Richard Davis’s double bass, the elastic anchor which holds the whole thing together. The charismatic drag queen of the title – an amalgam of six or seven different people, according to Morrison – is a wonderfully elusive construct around whom a rich cast of characters spin. Although his lyricism has never been more colourful or evocative, the key line is a simple one: “Say goodbye.” Madame George is one long letting go: to time, place, people; above all to innocence. It ranks among the most beautiful and heartbreaking farewells in popular music.

“To be born again / To be born again / From the far side of the ocean,” Morrison sings on the title track, signaling a personal reinvention; not only from his new home in America, but of rock music entirely. Astral Weeks is where it really begins. Morrison mixed the acoustic folk he had been playing in Boston coffee shops with a new jazz ensemble, featuring musicians who had played with the likes of Miles Davis, Frank Sinatra, Charles Mingus and the Modern Jazz Quartet.

Morrison showed the band his acoustic songs and told them to add what they felt. The classical guitar and flute flutter between string arrangements, Morrison’s spiritual poetry dancing atop, while Richard Davis’s double bass drives straight through, grounding it all. The songs are loose and free.

Astral Weeks was an insane idea: a largely improvised 47-minute jazz-folk song-cycle that wed a passionate spirituality to tales of Belfast’s most pronounced outcasts: junkies, transvestites, and disenfranchised souls of every variety. In its way, Astral Weeks was every bit as subversive and daring as the Velvet Underground’s thematically similar White Light/White Heat, released the same year. In some ways it was more so. While the Velvets swathed their tales of deviance and deprivation inside apocalyptic walls of feedback and dissonance, Van went the other way, with gentle, slow building beauty eerily offsetting the desperation of the album’s inhabitants.

Astral Weeks was an inarguably masterful record, but its baroque, drawn-out tales held little in the way of commercial promise.

There’s no other record like Astral Weeks. Its 47 minutes seem to be over in the blink of an eye, leaving you questioning everything you knew about music.

Moondance

Van followed it up with Moondance, an album full of brief, catchy, and often spectacular songs, including two unimpeachable classics: the rough and ready “Caravan” and the borderline transcendent slow burn “Into The Mystic.” The album was justifiably a million-seller, and from that point forward Van remained a bona fide commercial proposition as well as an artistic one,

Moondance is based around punchy R&B and concise pop songs. Side one is packed with five outstanding compositions; the title track, where Van plays Sinatra, is the most well known, but ‘Crazy Love’ is pretty, ‘Caravan’ is jaunty, ‘Into The Mystic’ is lovely and esoteric, while ‘And It Stoned Me’ is all of the above.

While Astral Weeks was a loose exploration, Morrison ditched the jazz ensemble for a new band for its follow-up. Moondance is far more structured, though he hides that with the freewheeling imagery of gypsies and idyllic county fairs. His spirituality is in full force here, from the baptism of “And It Stoned Me” (“Oh the water/Let it run all over me”) to the gospel of “Brand New Day.”

Morrison followed the loose abstractions of Astral Weeks with the precise opposite – a collection of tight, honed, radio-friendly blue-eyed soul made with the crack band of local musicians he had assembled near his then home in Woodstock. The 10 tracks on Moondance offer up an embarrassment of riches, but the killer cut is this mysterious tale of being “born before the wind, oh so younger than the sun”, and sailing the “bonny boat” into some sublime metaphysical harbour. Pinned down by Morrison’s rattling acoustic rhythm guitar, John Klingberg’s propulsive bass, and the totemic foghorn, Into the Mystic provides the spiritual heft on an album more concerned with transmission than transcendence.

Moondance would define what people would come to expect from a Van Morrison record: the swinging blue-eyed soul of an Northern Irish folk rocker enamored with early R&B. Side 1 is stacked with many of his best known songs: “And It Stoned Me,” “Moondance,” “Crazy Love,” “Caravan” and “Into the Mystic.” And side 2 is just as good. The dual saxophones of Jack Schroer and Collin Tilton keep the music from veering too far off into other genres, pulling the country rock of “Come Running” and the bluesy “These Dreams of You” right back into Morrison’s signature style.

His Band and the Street Choir

Van Morrison seemed to have aged quite a bit by 1970. He began writing and producing everything himself, relying heavily on song structure instead of the jams of Astral Weeks. His Band and The Street Choir is a confident step in the same direction as Moondance, but Morrison loosens up his grip to create a freer, more organic record — even leaving in some of the studio chatter. Moondance and His Band, were released in the same year, are like twins. They share a lot of the same genetic makeup, but they both pull in different directions, eager to prove themselves.

You know how the second side of Moondance was pleasant but unmemorable?His Band And The Street Choirs essentially is an entire album of the same thing – nicely arrangements, delivered in Van Morrison’s unmistakable voice, but the song-writing isn’t as sharp as on his other early albums. His Band And The Street Choir is generally grouped with the surrounding albums – Moondance and Tupelo Honey are as part of the domestic trilogy, chronicling Morrison’s life with Janet Planet in Woodstock in upstate New York.

Only a couple of the tunes from His Band And The Street Choir stick with me. Opener ‘Domino’ is a horn infused R&B song that’s still Van Morrison’s biggest hit in the US. And the closer ‘Street Choir’ has a big memorable chorus (“Why did you leave America?”) and more dramatic tension than the rest of the album. The remainder of Street Choir is often with less interesting lyrics than his best work.

There’s enough of Van Morrison’s enjoyable early sound to make His Band And The Street Choir interesting to fans.

Although always overshadowed by its multi-platinum sibling, His Band widens Van’s range. He runs through sax-filled soul rock on “Domino” (which topped even “Brown Eyed Girl” as his most successful single), folk on “Virgo Clowns,” and straight blues on “Sweet Jannie.” It’s loose and free but quintessentially Van.

Tupelo Honey

Although he moved to Marin County, California, to record Tupelo Honey, Woodstock, N.Y. is at the heart of the album. Lyrically, Morrison revels in his pastoral life that fell apart as Woodstock became a hippie destination after the 1969 festival.

Like many of his compatriots before him, Van Morrison relocated to America, although in his case it was due to a woman rather than a potato famine. While Van Morrison had lived in the U.S.A. since the start of his solo career, Tupelo Honey’s country textures make for his most American sounding album. Living in Woodstock, Van Morrison was living close to The Band, and they’re perhaps one influence on the rootsier sound here.

It’s perhaps symptomatic that the strongest tracks – opening single ‘Wild Night’ and the epic title track – are those closest to Van Morrison’s more typical R&B. If you’re not in the right mood, Tupelo Honey‘s agenda of doe-eyed domestic bliss can be nauseating, but despite the throwaway nature of several tracks the overall effect is often charming. The booklet artwork helps; Van, with his tight pants and little beard, looks like a cute Celtic mythological figure. The central song on Tupelo Honey is the gorgeous title track; it starts off with beautiful organ, joined by Van’s delicate vocal intoning “She’s as sweet as tupelo honey/She’s an angel of the first degree.” The other two epic tracks are also enjoyable; ‘You’re My Woman’ isn’t startlingly original, but carries through on a wave of euphoria, while ‘Moonshine Whiskey’ has a fluid catchy chorus that contrasts with the taut verses.

The standout tracks are the snappy lead-off single ‘Wild Night’, with a stylish bass entrance into the introduction, and ‘Old Old Woodstock’ which evokes the languid and rural tone of some of The Band’s work. The low point is ‘I Wanna Roo You’, which is even worse than the title suggests.

The lesser tracks do mesh into Tupelo Honey, as the whole album has a lightweight tone; a collection of mellow -tinged love songs. It’s enjoyable enough, but Tupelo Honey is one of Morrison’s lesser albums from his early catalogue.

The country waltz “(Straight to Your Heart) Like a Cannonball” finds him retreating to nature — “Sometimes it gets so hard/ And everything, everything don’t seem to rhyme/ I take a walk out in my backyard and go.” And although he abandoned the full-blown country-and-western theme he had planned for Tupelo Honey, the twang survived. “When That Evening Sun Goes Down” bops with honky-tonk piano and slide guitar.

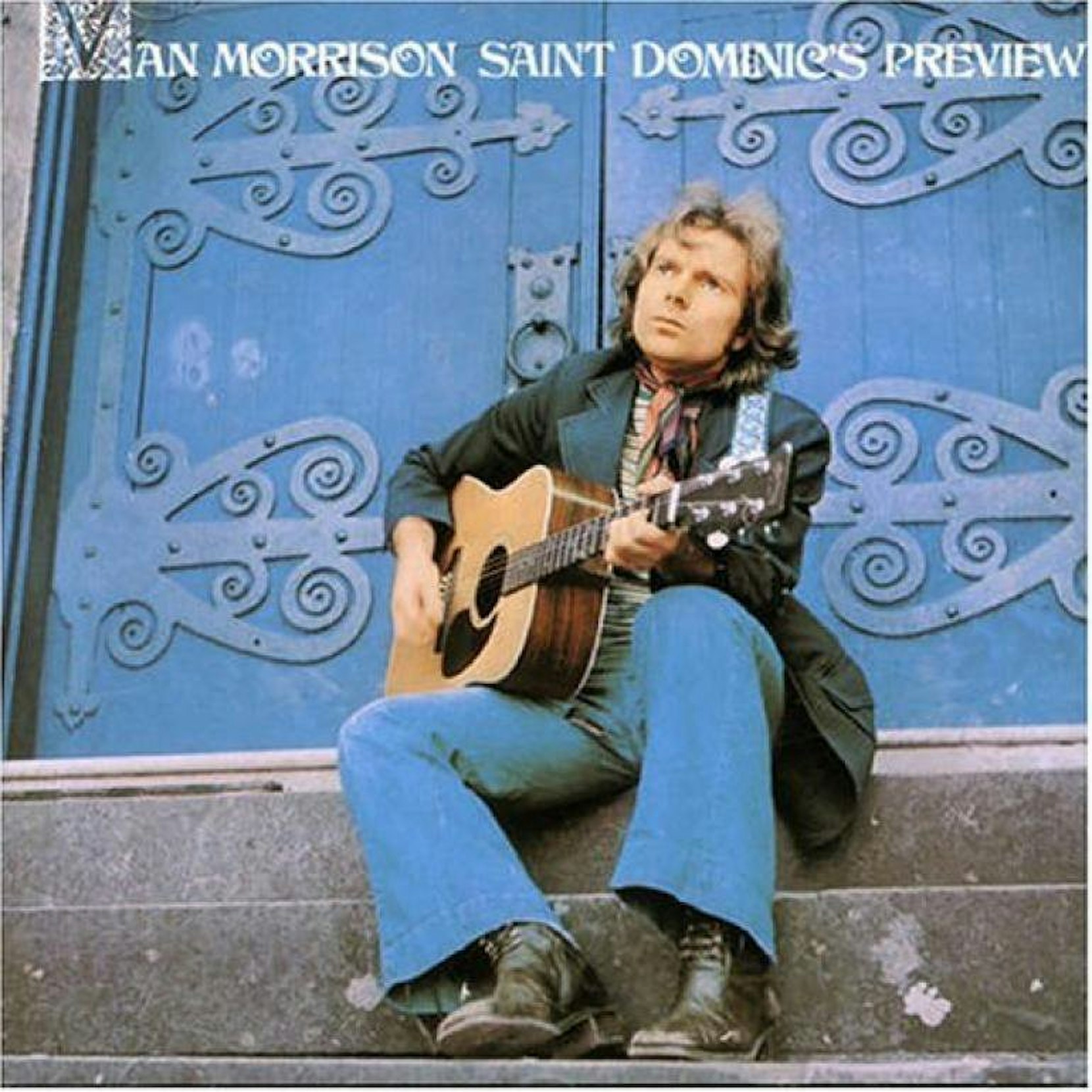

Saint Dominic’s Preview

Morrison genre hops more blatantly than ever on Saint Dominic’s Preview. He comes out swinging on the opener, “Jackie Wilson Said,” awash with saxophones and one of the catchiest hooks Morrison has ever written. But he wastes no time switching to the flute-heavy “Gypsy” and the Ray Charles jazz of “I Will Be There.” Morrison plays each style so convincingly, it’s barely noticeable how wide he’s reaching. But these three are really just an aperitif for what comes next.

Morrison’s superlative run of driving R&B singles in the early 1970s – Come Running, Domino, Blue Money, Wild Night had turned him into a US pop star, a development he professed to loathe, naturally. That particular populist strain of writing peaked with this frantic, appealingly odd slice of finger-snapping soul-pop from 1972’s Saint Dominic’s Preview. Paying homage to the great American R&B star, one of the few vocal stylists who could hold a candle to the Belfast Cowboy, Morrison is at his most unaffected and exuberant.

There’s no poetry here, just a string of “do-do-do-dos”, “bop-shoop-bops” and “dang-a-lang-a-langs” to express the sheer joy of being head over heels in love. Dexys Midnight Runners had the big UK hit with the song in 1982 , but Van’s remains the definitive reading. You can imagine the wee fellow high-kicking his way through it, letting it “all hang out”, and very possibly tearing the seat of his trousers in the process.

Three-minute marvels stood toe to toe with phenomenal existential meditations, such as the spectacular, harrowing ten-minute wonder “Almost Independence Day,” from 1972’s brilliant St. Dominic’s Preview.

The last four tracks contain some of Morrison’s deepest moments. The 11-minute “Listen to the Lion” is surprisingly sparse. He manages to draw out the song’s minimal lyrics, repeating lines like “I shall search my soul” and “Lookin’ for a brand new start.” He changes each line slightly as he repeats, not in a trance, but magnetically drawn to each one. The title track and “Redwood Tree” owe much to Morrison’s new life in California but with more spirituality than anything on Tupelo Honey. The latter culminates with the lines “Won’t you keep us all from harm/ Wonderful redwood tree” delivered joyously like a gospel Thoreau. Similar to “Listen to the Lion,” album closer “Almost Independence Day” is a winding stream-of-consciousness epic. With only a few repeated words, Morrison leaves the listener completely in awe.

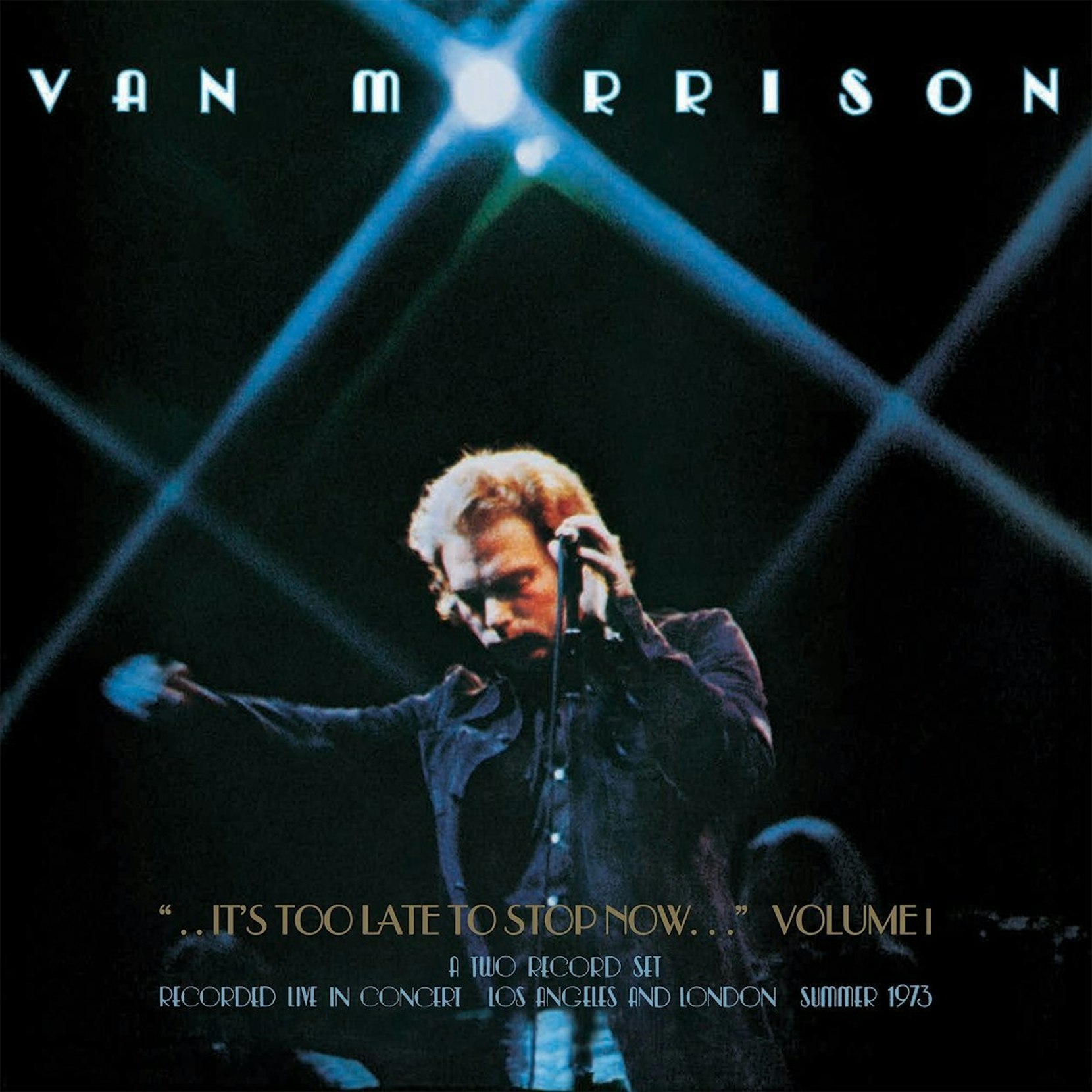

It’s Too Late to Stop Now

Morrison once said, “When I go into the studio, I’m a magician,” and working through this list, it’d be hard to argue against that. It seems obvious that he prefers the control of the studio to live performances where anything could go wrong. Even now, he has a reputation as an inconsistent performer, offering little to no banter between songs and often refusing to play the hits. But when he was on, he was untouchable.

It’s Too Late to Stop Now is Morrison’s Live at the Apollo. He fully embodies the soul singers he worshipped to deliver definitive versions of some of his songs — looser than ever, throwing ad-libs like a preacher speaking in tongues. Van runs through his classics like “Domino” and “Wild Night” with feverish energy, even singing along with the horns on “These Dreams of You.” A few times on the record, he catches his breath with slower tunes like “Cypress Avenue” or “Saint Dominic’s Preview” before jumping right back with fire. The maddening energy peaks on “Gloria,” where Morrison shows himself transformed from garage-rock singer to showstopping rhythm-and-blues man.

Morrison’s peerless double live album, It’s Too Late to Stop Now, is revisited this month in an expanded box set. Recorded during his 1973 tour, it captures him at a career peak, performing with the 11-piece Caledonia Soul Orchestra, a superlative band augmented with two horn players and a string quartet. The new material – 45 tracks – only serves to emphasise the jaw-dropping power and versatility of Morrison in full flood. It includes two previously unheard versions of Listen To the Lion, his epic incantation from Saint Dominic’s Preview; the one recorded at the Rainbow in London just about shades it for sheer vocal abandon, not to mention Bill Atwood’s soaring trumpet part. The song itself is the ultimate expression of Morrison’s compulsion to heed the internal voices that drive his music, the seemingly painful search for his inner lion. Over a slow, stop-start shuffle, the words are pared to a bare minimum. “I will search my very soul,” is the digested read; this is all about sound and feel. Many years later Morrison described it as “a song about me. Probably the only one”.

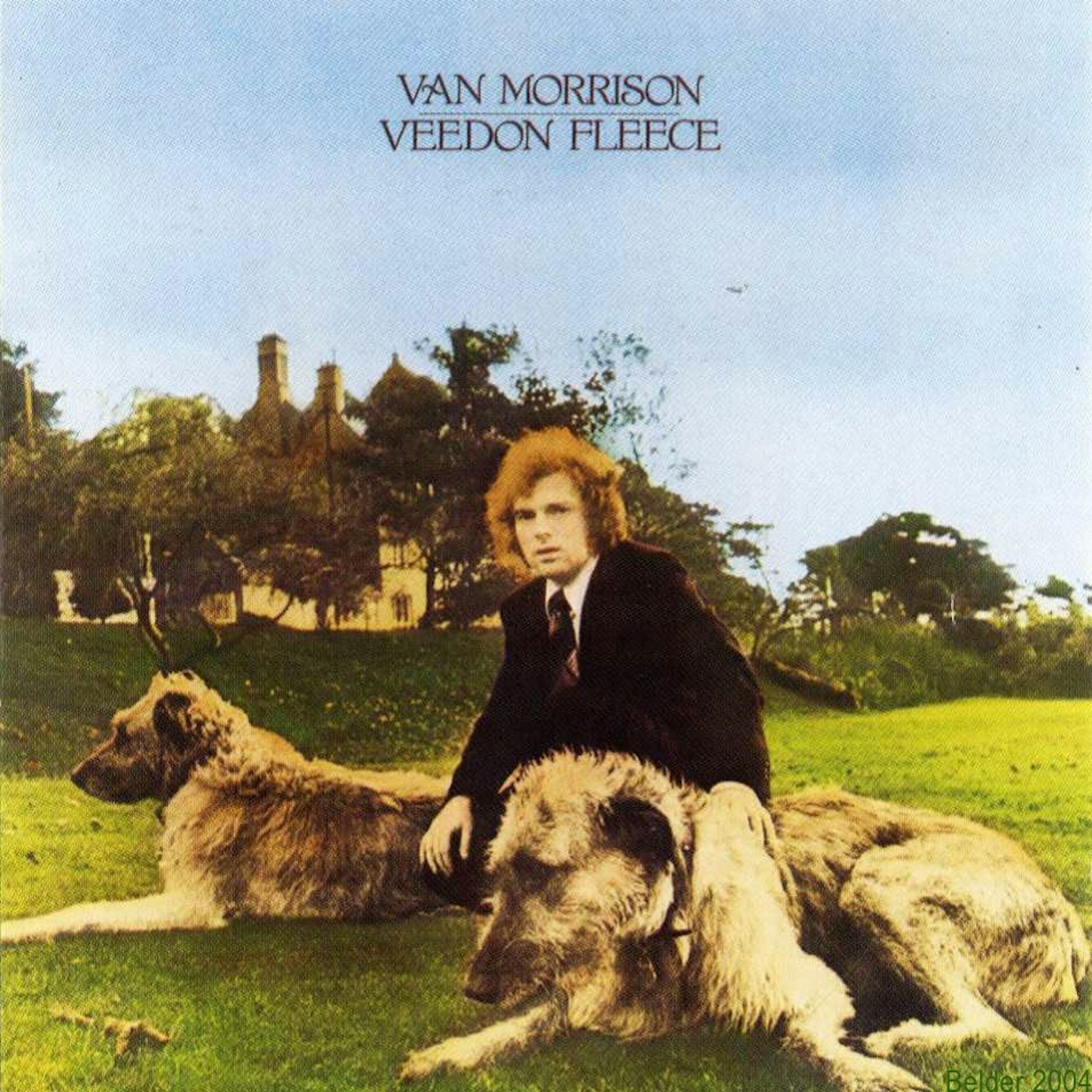

Veedon Fleece

Veedon Fleece is the ultimate hidden gem of Morrison’s catalog. Following the dissolution of his marriage, he returned to Ireland for first time since 1967. But Veedon Fleece isn’t really a breakup album Morrison already had a new fiancee at the time of his trip. It’s the sound of a man at a crossroads in his life, a wanderer coming home after a self-imposed exile, during which he failed to find a permanent place for himself.

Eventually, Van’s more meditative, experimental side became dominant again, resulting in both his best ever work and his most disappointing commercial results. 1974’s Veedon Fleece was a return to the geographic and emotional terrain of Astral Weeks, a Gaelic preoccupied masterclass packed with more melancholy, longing and despair than a mass audience was prepared to embrace. Its commercial failure would send a demoralized Morrison into a multi-year hiatus from releasing music. It is perhaps his greatest ever work.

After moving to America in 1967, Morrison spent the next six years in exile from Ireland. On his return in 1973 for a holiday, he immediately found the muse rapping at his window. He flew back to his home near San Francisco with a hatful of strange and beautiful songs, infused with Celtic twilight and preoccupied with a grail-like object that gave his next album its title but the significance of which even Morrison has since been unable to adequately explain. Reminiscent of Astral Weeks in its instrumentation, flow and questing spirit, Veedon Fleece is one of his greatest works. Any selection from the album is bound to be representative rather than definitive, but this brooding, contemplative march is a highlight, inspired by Morrison’s visit to the Wicklow town of Arklow, his head “full of poetry”. James Rothermel’s high, lyrical recorder soars over “God’s green land”, and when the strings swoop in at the start of the third verse, the force of the music perfectly conveys the gravitas of Morrison’s “soul-cleansing” excursion.

Veedon Fleece was the last album from Van Morrison’s initial run of solo records; subsequently he went into semi-retirement for three years, only emerging to appear in The Band’s The Last Waltz. In some respects, it’s almost the completion of the circle begun with Astral Weeks; , Veedon Fleece is more steeped in acoustic mysticism than any of his releases since Astral Weeks, and it’s similarly loose in feel. It’s also more noticeably more Irish than anything he’d released previously; there’s little R&B here, using more folk-oriented, acoustic instrumentation, and the lyrics reference William Blake and figures from Irish mythology.

The songs that take place in America deeply contrast with his descriptions of Ireland. “You can’t slow down and you can’t turn around/ And you can’t trust anyone,” he sings on “Who Was That Masked Man.” That paranoia comes right before the sunny description of Ireland on “Streets of Arklow” where he sings, “And our souls were clean/ And the grass did grow.”

Side 2 especially basks in the warm nostalgia of home with songs like “Cul de Sac” and “Country Fair.” On “You Don’t Pull No Punches, But You Don’t Push the River,” Morrison describes the search for the mythical “Veedon Fleece,” but musically he’s not searching, for the first time in years. He mostly treads through the jazzy folk he once covered on Astral Weeks, sounding more confident than ever.

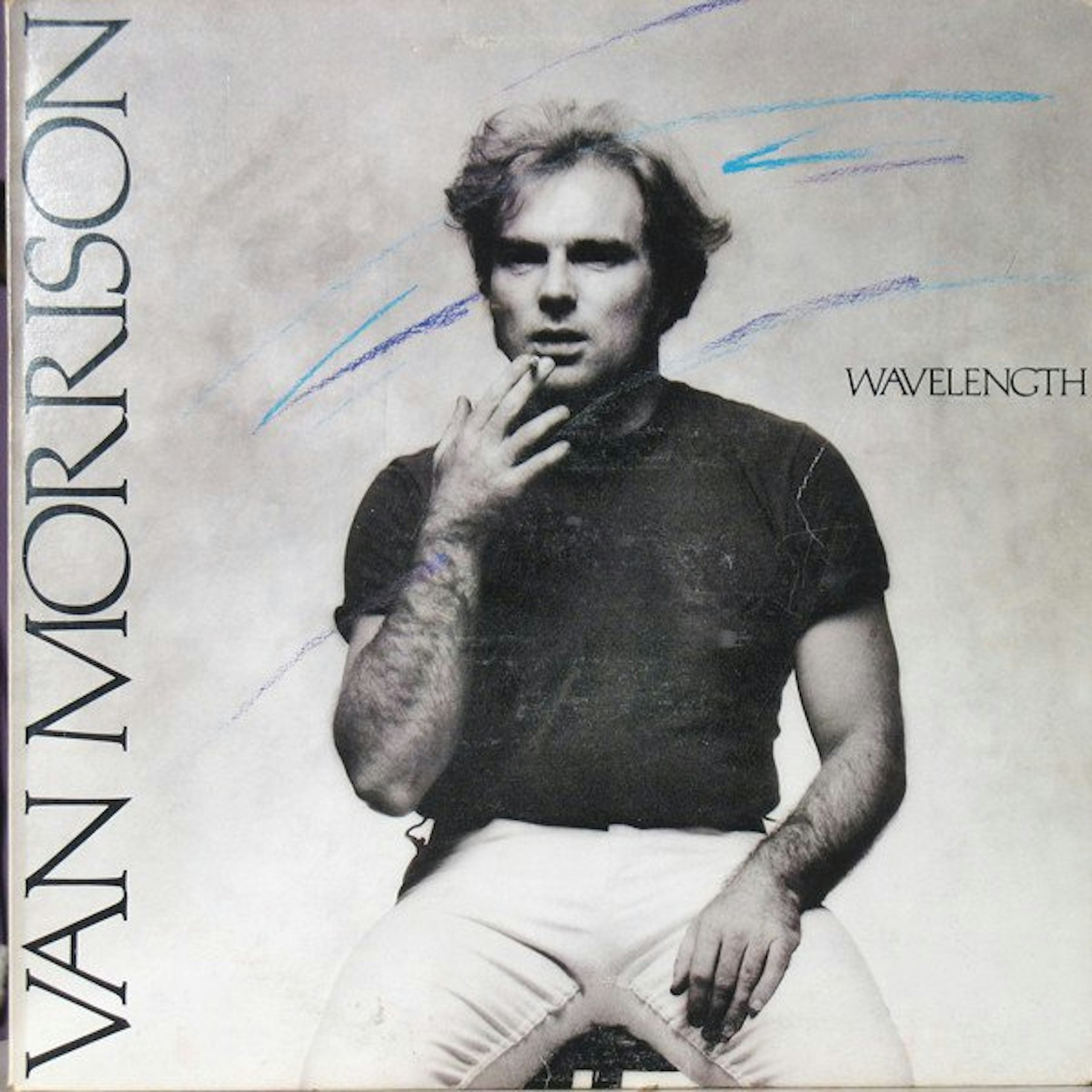

Wavelength

Wavelength immediately showers you with warmth. “So glad you made it, so glad you’re here,” Morrison sings on opener “Kingdom Hall,” the perfect greeting to what might be his most accessible record, packed start to finish with pop-rock classics.

Wavelength is Morrison’s first attempt at incorporating synths, but it’s still firmly a ‘70s record. The title track swims in warm synths, courtesy of Van’s former Them bandmate Peter Bardens, but they’re never the star. The guitar is high in the mix, right beneath Morrison’s voice and the gospel harmonies.

The Band’s Garth Hudson bookends the album with electronics, tearing through a keyboard solo in “Kingdom Hall” and adding grand synths to closer “Take It Where You Find It,” but the organ and accordion on “Venice U.S.A.” keep Wavelength from wandering too far toward the sky. The album doesn’t rely too heavily on synths — it’s a balancing act that’s prevented the record from sounding dated almost 40 years later.

Like the albums that followed it, Wavelength is slick and commercial, and the style suits Morrison as his vocals are unique enough that a generic musical backing isn’t a problem. It does mean that Wavelength can’t coast by on atmosphere like some of Van Morrison’s previous work did; the album is a little monotonous in places, and some of the songs drag on too long, and it works best when he’s laying on the pop hooks.

There are pop hooks galore on pop songs like the title track and ‘Kingdom Hall’, while the short, punchy ‘Natalia’ is arguably the most memorable piece. The gentle ‘Hungry For Your Love’, with Morrison playing electric piano is melodic and memorable, while the most significant piece is the closer ‘Take It Where You Find It’, which slowly builds into a nine minute epic, with the refrain centering around “lost dreams and found dreams in America”.

After the tentative A Period of Transition, Wavelength is a step forward for Van Morrison; its more polished sound would be utilised for 1979’s career highlight Into The Music.

Into the Music

After the commercial success of Wavelength, Morrison looked inward, turning to spiritual writing in a new way. Songs like “Full Force Gale,” which features a slide guitar solo from Ry Cooder, and “Rolling Hills” show him embracing Christianity for the first time in his music. The strings played by Toni Marcus complement the lyrics beautifully, but his signature horn swells and sax solos are still there.

Following a directionless mid-to-late 1970s, Morrison wrapped up the decade with one of his most enjoyable albums, Into the Music, a breezy declaration of spiritual and musical regeneration. With a sensational new band, spearheaded by former James Brown horn player Pee Wee Ellis and freewheeling violinist Toni Marcus, he hit upon a powerful folk-soul hybrid which on the album culminated in a monumental 11-minute version of the 1950s standard It’s All in the Game. Van’s more accessible musical instincts were also back on track. The one-two punch of Bright Side of the Road (a minor hit in the UK) and this rousing declaration of being “returned to the Lord” is one of Morrison’s most uplifting opening sequences, and the most effortlessly immediate music he had made since the days of Brown Eyed Girl. Whether or not you care for the God-talk, Full Force Gale is an irresistible expression of rebirth, a punchy pop gospel testament which sweeps away any doubters.

His early records revolve around searching — for a home, for love, for meaning — but starting in the late ‘70s, he seems to have it all figured out. His point of view may change from album to album, but in the moment he delivers these perspectives as truth. And for that moment, you’ll believe him. In “Angeliou,” Morrison perfectly sums up why we listen to his records: “It wasn’t what you said/ But just the way it felt to me/ As I listened to your story/ About a search and a journey/ Somewhere inside/ Just like mine.”

Into The Music is a blue-print of the adult contemporary direction than Van Morrison would pursue during the 1980s, but the song writing is so sharp that it’s his best album. It’s slickly produced and loaded with backing vocalists, strings, saxophones, and other adult contemporary paraphernalia, but for these joyous songs the sensory overload approach works beautifully, like being swept away by a wave of intertwined sexual and spiritual power.

No Guru, No Method, No Teacher,

His preoccupations became steadily more spiritual in nature, although the bile of his industry-related frustrations never abated. It all came together on the stunning 1986 release No Guru, No Method, No Teacher, an astoundingly underappreciated album that Okkervil River’s Will Sheff writes about with great insight

Van’s last full-length masterpiece was No Guru, No Method, No Teacher, released 30 years ago. From its pointed title onward it found him shucking off many of the formal teachings that had infiltrated his music over the past several years – Christianity, Scientology, Rosicrucianism – to reconnect with his enduring muses: nature, pantheistic spirituality and a deep absorption with the past.

In the Garden brings all three themes together in six minutes of pure rapture. Morrison transports himself back to “the garden wet with rain” of Astral Weeks, taking the listener, trancelike, through what he later described as “a meditative process”. The music is unspeakably gorgeous, a wonderfully tensile ensemble performance lead by Jef Labes’ rippling piano motif, every quiver held in check through to the ecstatic climax, where Morrison turns the album title into a mantra. Though he tends to favour more workmanlike material in concert these days, this remains the transcendent high point of Morrison’s recent live appearances.

Typical of Van, that gorgeous and wistfully autumnal album commences with a memorably dyspeptic complaint: “Copycats stole my words/ Copycats stole my songs/ Copycats stole my melodies…” It’s a funny sentiment, but it’s not wrong. The litany of timeless artists who have borrowed liberally from the musical vocabulary Morrison created is enormous. It is fair to assert that the careers of everyone from Bruce Springsteen to Elvis Costello to Dan Bejar would look immensely different without the presence of Van The Man’s influence. It is nearly assured that none of them would disagree, but the fact of it remains wildly under reported.

I’m still forming an opinion on this, but so far I think it’s one of his better albums from the period, with earthier arrangements. Like a 1980s’ take on his spacier mode – akin toAstral Weeks or Veedon Fleece. ‘One Irish Rover’ is pretty, ‘Foreign Window’ is punchy with its memorable horn riff.

Common One

This 15-minute excursion from 1980s meditative Common One became the fulcrum of Morrison’s live shows for the next decade, an open-ended opportunity for the band to vamp and for he and Ellis to engage in extended call-and-response routines about topics as obscure as brass bands and Seamus Heaney’s publisher. Summertime in England is the deepest of Deep Van, an improvised jumble of some of Morrison’s most pressing musical, spiritual and literary preoccupations. Partly inspired by the open spaces of Miles Davis’s In a Silent Way, it’s a deeply ambitious, highly eccentric, improvised blend of snappy rhythm, hymn-like half-time passages, funky organ, vaulting strings and free-flowing horns.

The action moves from the Lakes to the Vale of Avalon as Morrison pictures Wordsworth and Coleridge “smokin’ up in Kendal”, evokes Mahalia Jackson coming “through the ether”, pays homage to Yeats, Joyce, Eliot and, of course, William Blake, and eulogises about a woman in a red robe – “high in the art of sufferin’” – with whom he plans an assignation in the long grass. The conclusion of all this magnificent madness? “It ain’t why, why, why – it just is.”

Into The Music was among Van Morrison’s most accessible efforts; its followup is among the least. Common One plunges directly into mystic spiritual territory, and with two songs passing the 15 minute mark there’s little in the way of pop hooks. Losing pianist Mark Jordan from the Into The Music band changes the feel of the record significantly; Common One is more open sounding and jazz oriented, with more room for improvisation from Van Morrison’s vocals, and the saxophone and trumpet.

The result is arguably the most divisive album of Van Morrison’s career, as its lengthy song structures push it close to jazz (as admirers would classify it) or easy listening (as its detractors would label it); and there’s justifiable grounds for regarding Common One as a flat-out masterpiece, a noble failure, or as an outright snooze fest.

While it’s not immediately compelling, the ambient atmosphere of the longer pieces is quite unique in Van Morrison’s catalogue. A couple of the shorter pieces are accessible enough; ‘Satisfied’, which Christgau accurately categorises as “the only vaguely fast one”, could have fit nicely onto Into The Music with its punchy R&B arrangement, while ‘Wild Honey’ is concise and prettily melodic, with a sentimental arrangement and lyric (“don’t you feel my heart beat/just for you”) that rubs up nicely against the more esoteric material. The more esoteric, fifteen minute material comprises of ‘When Heart Is Open’, a subdued improvisational piece based on Miles Davis’ In A Silent Way, and the more urgent ‘Summertime In England’, where Van Morrison rants about T.S. Eliot and William Blake. Add in the charming opener ‘Haunts Of Ancient Peace’, and there’s plenty of really good material here.

Common One takes some effort to decode, and it’s probably the least approachable album that Van Morrison ever made, but there’s plenty to enjoy for dedicated fans.

Avalon Sunset

Before Morrison’s long slide into genre exercises – a skiffle album here, a country record there, jazzin’ at Ronnie Scott’s – and the undistinguished collections of too-solid blues and R&B that have defined his music over the past two decades, he enjoyed a late-80s commercial renaissance with Avalon Sunset. The album marks the lush, string-drenched apogee of his preoccupation with a peculiarly British strain of ancient mysticism. Forget the singularly unlikely Cliff Richard duet (Whenever God Shines His Light) which finally got The Man on Top of the Pops, and head instead to this magnificent miniature Coney Island is an orchestrated gem over which Morrison recites – in thick east Belfast vernacular; check out the way he says “face” – an autumn bird-watching trip through the County Down where the “craic was good” and so, apparently, was the grub: “Stop off at Ardglass for a couple of jars of mussels and some potted herrings, in case we get famished before dinner”. Somebody once tracked the route taken in the song and concluded that Morrison must have deployed William Burroughs’ cut-up technique on his road map, but such literalism misses the point. This is a journey into the heart of life’s simple joys, a note-to-self to seize contentment when it appears, even in such seemingly mundane pleasures as “stopping off for Sunday papers at the Lecale District”. A mere 123 seconds it may be, but Morrison’s eternally restless soul has rarely sounded at such peace. “Wouldn’t it be great if it was like this all the time?”

Avalon Sunset, Van Morrison’s 19th studio album, was a commercial success, and his fastest album to reach gold status in the UK. But while it attracted more attention than usual, it feels like Morrison is treading a well worn path by this point, To Van Morrison’s credit, he was able to write a popular standard on Avalon Sunset, unusual for a pop artist into the third decade of their recording career; ‘Have I Told You Lately’ was popularised by Rod Stewart, and has been co-opted as a popular wedding tune, but it’s a love song to God.

Similarly, the other songs that deal most explicitly with faith are also strong. It’s possible to dismiss the Cliff Richard duet ‘Whenever God Shines His Light’ as mawkish, but I like the contrast between Richard’ boyish tenor and Morrison’s emotive yelp. ‘When Will I Ever Learn to Live in God’ is tuneful and thoughtful.

Avalon Sunset is a solid album with no obvious throwaways, but besides these highlights I don’t have a whole lot of use for it; it’s mostly Van Morrison dispensing wisdom over a smooth backing. Unless you’re a hardcore fan, you’re probably better off finding the album’s best songs on a compilation.

Beautiful Vision

Beautiful Vision is one of Van Morrison’s most settled, comfortable albums, like a calmer take on the Into The Music sound, and it’s relatively insular with its low key explorations of spirituality and Irish heritage. Even if he’s sometimes treading water musically, there are plenty of great songs here, and it’s one of his more consistent, most substantial records, even if it’s less adventurous and less universal than his earlier work.

Beautiful Vision is one of Van Morrison’s most settled, comfortable albums, like a calmer take on the Into The Music sound, and it’s relatively insular with its low key explorations of Christianity and Irish heritage. But even if he’s treading water musically, there are plenty of great songs here, and it’s one of his more consistent, most substantial records, even if it’s less adventurous and less universal than his earlier work. Guests include Mark Knopfler, who plays guitar on ‘Cleaning Windows’ and ‘Aryan Mist’, while Morrison himself plays piano on the closing instrumental ‘Scandinavia’, where his sprays of notes are melodically compelling.

Enforcing an initial reaction that Beautiful Vision is bland and uninteresting, at least a couple of these songs are abjectly uneventful – the monotonous title track and ‘Aryan Mist’ both wander past without adding anything to the record. But digging deeper, there are a couple of catchy potential singles in the form of ‘Cleaning Windows’ and ‘Dweller On The Threshold’, the former a seemingly autobiographical tale from Van Morrison’s days in Belfast inspired by R&B, and the latter balancing wistful lyrics with a fast tempo. The standout track, though, is ‘Across The Bridge Where Angels Dwell’, where R&B, jazz, and gospel are fused into a glorious whole, Van Morrison’s voice floating above the female backing vocals. The two Celtic influenced pieces, ‘Northern Music (Solid Ground)’ and ‘Celtic Ray’, give the album a solid beginning,

The insular world that Morrison creates here isn’t ideal for neophytes, but Beautiful Vision is like a more mature, calmer version of Into The Music, and it’s not as far from that album’s greatness as it may seem on first impression.

Hard Nose The Highway

You can’t go too far wrong with Van Morrison’s 1968-1974 period; Hard Nose The Highway is justifiably reckoned as one of his lesser albums from the era, but it’s still an enjoyable listen. If St. Dominic’s Preview was a brilliant summation of Van Morrison’s career up to that point, then Hard Nose The Highway is arguably a predictable retread.

The record also has more of a smooth, jazz-inflected feel, and it’s a little blander than usual, but it’s still sonically creative in the opening ‘Snow In San Anselmo’, which is one of the weirder successes in the Van Morrison catalogue. The two covers, the traditional British ballad ‘Wild Mountain Thyme’, referred to here as ‘Purple Heather’, and the more bizarre choice of ‘Bein’ Green’ are also an indication of Van Morrison running out of ideas, but they’re nicely performed, and none of the above objections detract from the fact that most of the songs on this album are perfectly solid.

Despite the overall feeling that it’s a relatively minor work, the major issue with Hard Nose The Highway is simply that the ten minute track ‘Autumn Song’ drags more than it should; a pleasant but generic jazz tune is stretched out to unnecessary proportions, far less interesting than the previous record’s ‘Listen To The Lion’. The lyrical agenda of ‘The Great Deception’ is blatant (“Have you ever heard about the great Rembrandt/Have you ever heard about how he could paint/And he didn’t have enough money for his brushes”), but works fine musically.

The main appeal of Hard Nose The Highway is the pair of opening tracks; ‘Snow In San Alselmo’ is one of Van Morrison’s best arty tracks, with a eerie feeling and weird choir, while ‘Warm Love’ is one of his best commercial songs, with an accessible melody and utilising his pretty upper register. The title track is perfectly solid, while he also manages to bring something new to the somewhat over-used ‘Purple Heather’.

Hard Nose The Highway isn’t Van Morrison’s strongest album by any stretch of the imagination; it’s the quietly under-achieving record between two milestones, but Morrison was in such good form at this time that even his under-achievements are worth hearing.

TB Sheets

During Van Morrison’s spell in Them, the brutally, brilliantly reductive Belfast band he fronted between 1964 and 1966, there had been glimmers of an artistic sensibility at odds with the turbo-boosted dockside R&B of songs like Gloria and Baby Please Don’t Go. On My Lonely Sad Eyes, Hey Girl and an aching cover of John Lee Hooker’s Don’t Look Back, Morrison was reaching for something deeper and more revelatory. It wasn’t until he made his first solo recordings in New York with Bert Berns in 1967, however, that he began forging a distinct creative identity. The antithesis of the jaunty Brown Eyed Girl, TB Sheets is the first great Morrison immersion: 10 minutes of crawling, bloodied blues, sticky with the sweet stench of decay. Taking cues from gnarled old death songs like TB Blues, Morrison conjures something entirely idiosyncratic. The “Julie baby” dying of tuberculosis was, according to various sources, either an old high school friend, his London landlady or a work of fiction. Whoever she may be, Morrison delivers us, with unremitting focus, into her fetid room, creating a suitably claustrophobic, choking musical backdrop of stabbing organ, stinging blues licks and searing harmonica. His agitated death-watch veers between compassion (“I cried for you”), impatience (“I gotta go, I’ll send somebody around later”), awkward empathy, guilt and mortal dread. When words fail, he snuffles at the window like a hunted boar. When the recording was over – apparently; perhaps apocryphally – Morrison burst into tears. Not an easy listen, but grimly unforgettable.

Them

Every Van Morrison collection needs something from Them. Both of their albums, The Angry Young Them and Them Again, were recently reissued, but if you manage to find one of the many compilations out there, you get the bonus of their non-album singles like “Baby, Please Don’t Go” and “Richard Cory.”

In the two years they were together (1964 – 1966), Them recorded garage rock classics like “Gloria” and “Here Comes the Night.” The blues rock of his youth remains part of Morrison’s career even now, although tightened up considerably. Them’s music is an important document of a burgeoning young rock star about to become the Van Morrison we all know today.