Even though lots of people sell as many or more records as he does, Sly Stone is probably the most influential musician over the years. He changed the face of soul, and co-authored, with Jimi Hendrix, black psychedelic music, It is not only Sly’s string of hit singles, and the remarkable achievement of ‘Riot’, which confirms his musical genius.

When he was eight, he cut his first record, with three of his siblings—all of whom would later start bands and then be members of the Family Stone. All of them were talented. But Sly was a prodigy, mastering keyboards, guitar, drums, and bass by the time he turned eleven.

It is sometimes difficult to see the extent of Sly’s genius. In June 1967, San Francisco’s counterculture dreams were peaking when a local music scenemaker named Sylvester ‘Sly’ Stewart led a motley-looking interracial, mixed-gender crew, half of whom were from his own family, into a recording session for Epic Records.

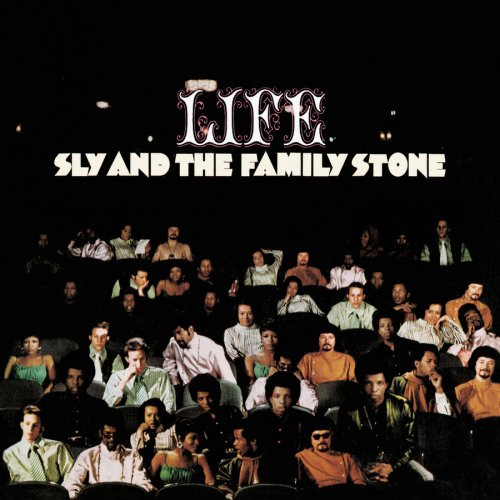

Over a few scattered hours, the group that became known as Sly and the Family Stone cut their debut in 1967, ‘A Whole New Thing” live in the four-track studio. Led by singer-songwriter, producer, and multi-instrumentalist Sly Stone, and included Stone’s brother and singer/guitarist Freddie Stone, sister and singer/keyboardist Rose Stone, trumpeter Cynthia Robinson, drummer Greg Errico, saxophonist Jerry Martini, and bassist Larry Graham. It was the first major American rock group to have a racially integrated, male and female lineup

In high school, though, he kept mostly to the guitar as he joined local groups. A doo-wop outfit called the Viscaynes featured him and a Filipino pal in a then-unusual interracial lineup. They even cut a few singles for the local market, like “Yellow Moon”. Studying at Vallejo Junior College, Sly honed his skills, picked up the trumpet, and mastered composition and theory. The opening and closing of “Underdog” on ‘A Whole New Thing’ archly reflects that: recasting the “Frère Jacques” melody as a horn riff in a minor key, Sly tips his hat to Gustav Mahler, whose First Symphony did the same thing repurposing the kids’ tune as…wait for it…a funeral march.

Young Sly had the patter and the fire to succeed as one of the DJs who redubbed their station K-SOUL. He stirred popular white bands into the mix he thought would fit because of their obvious R&B influences, like the Animals, the Stones, and the early Beatles. It’s almost like he was on a mission to enact the musical equivalent of racial integration, mutual acceptance and interplay. And it apparently worked: He upped white audience numbers without losing black listeners, Later, Sly would aim to emulate their feat with his own music and succeed brilliantly… for a while.

Meanwhile, the local rock scene was probing exciting new shapes and sounds, the first waves of psychedelia. It was largely white kids, but that didn’t bother Sly, who was voraciously absorbing everything he heard and encountered.

Donahue, an ambitious giant of a man, first heard the teen at a Vallejo sock hop, then hired him to ramrod the house band at his big concerts, like the 1962 Chubby Checker “Twist Party” that landed at the humongous Cow Palace, usually the venue for (what else) livestock shows. That night it held 17,000 fans, making it the first big-time rock concert in Bay Area history.

Sly was quickly slotted in as Donahue’s go-to guy on stage and in the studio. He was getting a musical education that filled his toolbox with versatile skills he’d soon use for himself. Since the music biz’s earliest days, songs pushing new dances had been a reliable way for black artists to get to mainstream white audiences. No doubt young Mr. Stewart filed that knowledge to tap into for “Dance to the Music”

But he also produced an eclectic batch of Bay Area faves. like The Great Society which features Grace Slick unspooling an obbligato line of raga-ish vocalese; he also apparently ran the sessions for “Someone to Love” Both cuts make clear why Slick would jump ship and join Jefferson Airplane; as she once put it, “They had a real rhythm section.” Sly watched drummer/singer Jan Errico with real interest: there were very few females playing instruments in rock bands, never mind drums, and singing too. As it happened, she had a brother-drummer named Gregg, who would join the Family Stone.

Preston’s year-long gig on the TV show Shindig!, which introduced him to a huge audience, had just ended when the record was released on a major label. It didn’t exactly burn up the charts, but the pair continued to collaborate, For years they’d grace each other’s records with guest shots, refusing to be hemmed in by musical styles and expectations,

Once Sly merged his band (Sly and the Stoners) with his brother Freddie’s (Freddie and the Stone Souls), the Family Stone was born.

They found a home base to hone their music in Redwood City, a club called (nudge-nudge-wink-wink) Winchester Cathedral. A few months of that, and they’d forged a unique sound and a phenomenal stage show. Not surprisingly, Sly used down time at Autumn’s studios to record the band. And so the 24 cuts compiled on ‘Sly and the Family Stone offer tantalizing insights into how the band evolved.

A rousing early iteration of “Dance to the Music” pumped by Graham’s already-distinctive bass and a blistering guitar solo. But the hard-driving soul of “I Ain’t Got Nobody” their first official single, got them the ear of an Epic employee, who tipped Dave Kapralik, head of A&R. They were so engulfing and powerful onstage that he signed them immediately, then became their manager. And into Epic’s studio they went. The album flopped. But their manager and label head pressed Sly to write hit singles—the ingredient they were sure was lacking on their first album. So he did: ‘Dance to the Music” and ever since, ‘A Whole New Thing’ has been dissed or ignored.

“A Whole New Thing’ (1967)

It’s ear-opening to check out how far they’d developed their winning combo of musical sophistication, wry humor, and gutsy immediacy on ‘A Whole New Thing’. It may have been a four-track recording done live, but the stereo image bursts at the seams with richly layered sonics, showcasing Sly’s adept production skills as well.

It kicks things off with a protest song that doesn’t just nod toward Mahler but pumps its anti-racism message up with Larry Graham’s burbling bass and Greg Errico’s funky drumming, sharp-creased horns, and vocals worthy of Motown—which duly took lessons from it. The album heralds the sound of the Family Stone’s future funk with Graham’s near-solo spot and the ba-boom-boom scatting following the tongue-in-cheek TV Indian theme from the horns. “Run, Run, Run” opening with surprising melodica and xylophone, finds Sly refracting the hippie vs square world through his black eyes and inventive twists: the middle vocal section riffs off the Turtles, and listen for the Mothers of Invention touches.