With the release of “Brain Salad Surgery”, Emerson, Lake and Palmer had outgrown any initial perceptions that they were simply a trendy supergroup possessing limited commercial appeal. Instead, they were now finding themselves well positioned on the precipice of mainstream success. To be sure, they were still seen as something of a phenomenon; after all, Keith Emerson’s over-the-top keyboard antics, Greg Lake’s engaging vocals and Carl Palmer’s thundering percussion placed them within a decidedly higher musical pantheon, one that found them capable of attracting audiences of stadium-sized proportions.

Thanks to the success of their preceding live album, “Pictures at an Exhibition”, Emerson, Lake and Palmer had become accredited practitioners of a prototypical prog/classical crossover configuration, one that boded well for continued accreditation. Emerson had initiated that stance with his previous group, the Nice, only to have it further realized with ELP, courtesy of a refined and sophisticated sound accompanied by a solid instrumental undertow. The fact that the three musicians were capable of such an achievement had never been in doubt, but with “Brain Salad Surgery“, that reputation was indelibly entrenched in both pedigree and practice. The group had bought a cinema in Fulham, which they renamed the Manticore Cinema, and they rented it out as storage and rehearsal space to groups. But in the rehearsals for “Brain Salad Surgery“, they left their gear set up on stage and rehearsed it as if playing a live show.

Released on November 19th, 1973, “Brain Salad Surgery” didn’t contain the same variety of instantly accessible music that songs like “Lucky Man” and “Take a Pebble”—both culled from ELP’s eponymous debut—had offered early on. Like the ELP albums that followed in its wake, it bore a sound that was increasingly more complex, built on majestic motifs that were far removed from what most people would have ever identified as an easy listening experience. Their fourth album, 1972’s Trilogy, had reached Number Two in the UK and Number Five the USA, but in rehearsing and arranging the music for “Brain Salad Surgery, ELP made a decision to pursue a quite different approach. “Music technology was really expanding,” Lake explained. “Tape recorders were going from 8-track to 24-track.

And yet, it did have one singular song in particular—“Still…You Turn Me On,” a wistful ballad that Lake sang with a certain soothing assurance is one of his dreamiest acoustic songs. These had always provided dynamic contrast to ELP’s power play, both live and on record, and here Emerson joins in on harpsichord. Was the idea that the song was addressed to a certain person in the audience?. Given the fact that Palmer played no part in its recording, the idea of releasing the track as a single was nixed entirely. So, too, because at least half the album consisted of elegiac suites (dubbed “Impressions”), part of an extended work titled “Karn Evil 9,” there was very little material that could be considered a possible choice as far as selection as a single. “Benny the Bouncer,” composed by Lake and his one-time King Crimson colleague, lyricist Pete Sinfield, might have been an option, but the hokey theme and fickle approach didn’t really represent the band’s artful approach, their purpose or their prowess, and, as a result, it was never a real contender.

The album opens in a blaze of light, though, with a flamboyant version of William Blake and Hubert Parry’s “Jerusalem“, with Palmer playing gongs and timpani, and executing lavish multiple tom-tom rolls around his stainless steel kit. Emerson garnishes proceedings with exultant Moog clarion calls, while Lake’s magisterial voice holds the middle ground. “Jerusalem” was the consensus pick, but the BBC quickly vetoed that idea due to its refusal to play anything that was perceived to be sacrilegious. Although the album reached the upper tiers of both the British and American charts and sold well enough to be certified gold the lack of a viable single seemed to hinder its overall possibilities. Palmer still laments the fact that “Jerusalem” was stillborn as far as a singles candidate was concerned. “We wanted to put it out as a single,” Palmer saying. “We figured it was worthy of a single…I think there was some apprehension [as] to whether or not we should be playing a hymn and bastardizing it, as they said, or whatever was being called at the time … We thought we’d done it spot-on, and I thought that was very sad…I actually thought the recording and just the general performances from all of us were absolutely wonderful. I couldn’t believe the small-mindedness…It got banned and there was sort of quite a big thing about it. These people just would not play it. They said no, it was a hymn, and we had taken it the wrong way.”

Another portion of the album initially presented a problem as well. “Toccata” was a piece Emerson had first considered for the Nice, but the idea of doing it with ELP hadn’t surfaced until Palmer suggested spicing it up with an extended drum solo. However, its complexity proved to be a handicap due to the fact that Lake didn’t read music and Palmer couldn’t find a musical score that adapted the piano arrangements for drums. Those difficulties were overcome, but the real problem lay in the fact that the publisher of the piece refused to grant the group permission to do an adaptation. That led to Emerson flying to Geneva to personally play the group’s arrangement for the publisher’s representatives, in hopes of persuading them to change their minds. The tack worked, and the publishers, duly impressed with what they heard, eventually allowed ELP to proceed. “Toccata” would eventually coalesce into a spectacular mesh of sound, fury, flash and finesse, a standout selection that ranks as one of the highpoint of the entire LP.

The aforementioned “Karn” suite became notable in its own right, due not only to the trio’s usual over-the-top instrumental antics, but also because the computerized voice featured in its third movement gives Emerson his only vocal credit of the entire ELP lexicon. Likewise, the second section of the first movement boasts the lyric that would become one of the most famous lines in the entire prog rock canon: “Welcome back my friends, to the show that never ends.” It would famously become the title of the band’s epochal three-LP live album a few years later.

“Brain Salad Surgery” is the group at the pinnacle of its powers,” says drummer Carl Palmer of Emerson Lake & Palmer’s fifth album. “It’s very well recorded and it was definitely one of our most creative periods. If I had to choose one of our albums, that would be the one.”

It’s a viewpoint echoed by his erstwhile bandmates. Keyboard player Keith Emerson sees it as a “step forward from the past”, which “represented the camaraderie of the band at the time”. Bass player and vocalist Greg Lake reckons that it was “the last original, unique ELP album”.

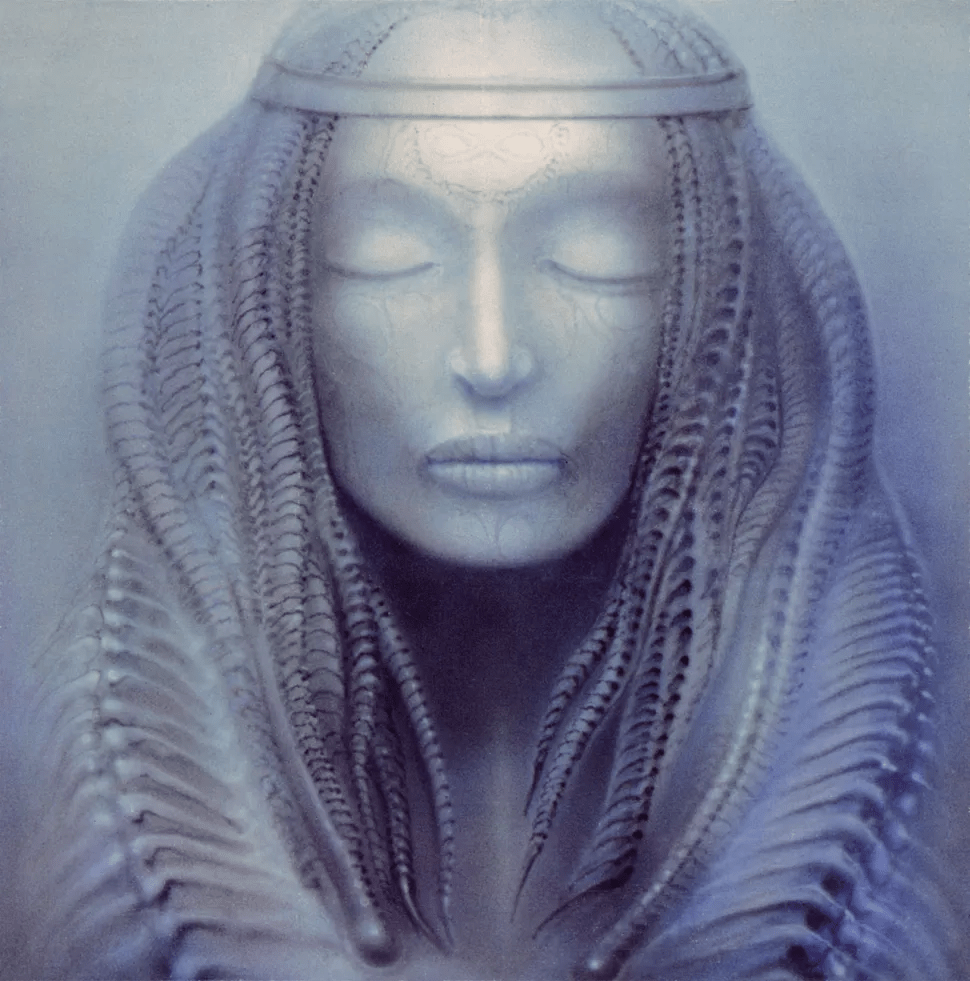

The fold-out cover sleeve, designed by the Swiss artist H.R. Giger, was also notable and, in fact, considered quite innovative as well. Given that the working title of the album had been “Whip Some Skull On Ya“—shorthand slang for fellatio—the skull triptych designs Giger was working on at the time seemed to find a perfect fit, even after the title was changed to Brain Salad Surgery.