Patti Smith had been kicking around the New York art scene since the late 60s doing everything from painting to acting to journalism to poetry. After co writing several songs for Blue Oyster Cult, with then boyfriend Allan Lanier, fronting a rock band seemed the next logical step. Her debut album was recorded in 1975 with John Cale as producer. The music owes much to garage bands of the 60s while being in step with the emerging punk bands who frequented the famous CBGBs where her earliest shows occurred. Where Smith stands out is in her dramatic often spoken delivery with the end results often described as art punk.

The album opens with Smith singing, “Jesus died for somebody’s sins, but not mine”. This line encapsulates Smith’s personality perfectly. This intro is actually from the beginning of her cover of Van Morrison’s Gloria. “Redando Beach” follows with a punk reggae sound that pre dated the ska revival by a couple years. “Free Money” is a flat out rocker and deserved to be a single.

“Kimberly” is a more commercial song which plays like a decadently dark version of Fleetwood Mac. The album’s highlight is the nearly 10 minute “Land” suite which couples a cover of “Land Of 1000 Dances” with Smith’s own “Horses”. Smith builds tension throughout the tune whipping herself into a frenzy

What makes the “Horses” album so great is the overall energy and looseness of the songs. The arrangements sound more like a live show would as opposed to being recorded in a sterile studio. Although the album was only a moderate seller at the time of release (#47), it would eventually go gold in many countries.

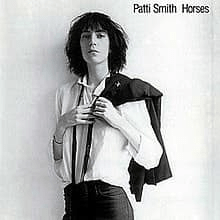

1975, “Horses”, then. A record that ends the year by popping up like a slap in the face. An impeccably black and white, impeccably sober cover, which by its aesthetic alone — a bit like Bruce Springsteen’s “Born To Run”, and shortly preceding the first Ramones — threw to the dump the airbrushed exuberances, the winged dragons, the neon titles and the dripping colors of Yes, Genesis, Uriah Heep and so on. But this graphic manifesto was not only one. Patti Smith’s entire artistic and poetic approach was screaming the end of the world before.

New York, then, was bankrupt. The city is dark, public services are creaking. On 42nd Street, the facades are crumbling under the signs of peep shows and the neon lights of sex shops, the sidewalks are teeming with prostitution, dealers are on the pavement. “The streets smelled of gasoline, sweat and heroin,” wrote journalist Pete Hamill. Times Square has become a dumping ground: collapsed junkies, corrupt cops, violence on every street corner. The Bowery is just a succession of seedy hotels, squats, lost silhouettes. But in this chaos, poisonous flowers grow, a scene is invented at CBGB’s: Television, Ramones, Blondie, Talking Heads, Richard Hell — a nickname chosen in direct homage to “A Season in Hell”. And Patti Smith in the centre, crazy about Rimbaud, falling in love with Verlaine, Tom.

With “Horses”, Patti Smith brings rock back to the urgency: it’s not a question of virtuosity, there, but of incantations, visions, poetry mounted on electricity. “Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine”: a whole world cracked in a single sentence. The music has just changed. More than a record, then. “Horses” becomes the standard bearer of a generation that refuses the spectacle for the naked truth. Ditch the Afghan vests for the Perfecto. A shady, poetic, electric, cultured scene: punk. And its echo would cross the Atlantic, influencing and educating London, from the Sex Pistols to the Clash, and then all of old Europe. Fair return.