Tom Waits middle-period albums–released on Island Records between 1983 and 1993—have been newly remastered from the original tapes and will be reissued on 180g vinyl this fall via Island/UMe. The series kicked off on September 1st, 2023, with Waits’ transformative creative breakthrough, “Swordfishtrombones” (1983), its sprawling sequel, “Rain Dogs” (1985), and the trilogy-completing, tragi-comic stage musical, “Franks Wild Years” (1987), It;s almost 40 years to the day that “Swordfishtrombones” was released, ushering in a new and critically acclaimed musical era for Tom Waits and his long time songwriting and production partner, Kathleen Brennan.

All these bulletproof songs, one after another: remembering Tom Waits’s extraordinary mid-career trilogy. the magnificent album sequence that began with “Swordfishtrombones”.

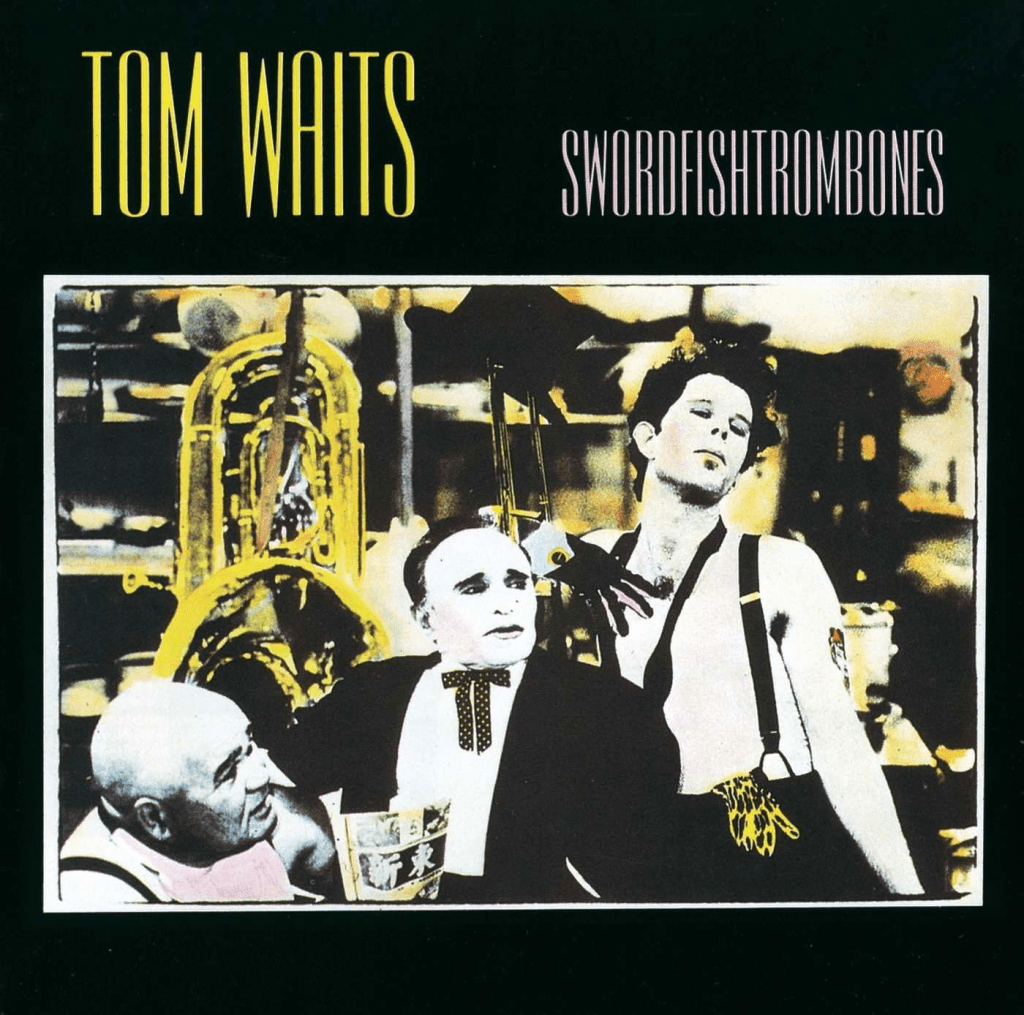

Tom Waits’s 1983 album, “Swordfishtrombones“, there is, in among a lot of fabulously unhinged musical experimentation (Tony Bennett described the record as “a guy in an ashcan sending messages”), a 90-second ballad of such tender beauty that it explains all the rest. The song was written for Waits’s wife, Kathleen Brennan – “She’s my only true love/ She’s all that I think of, look here/In my wallet/That’s her” – and named after the town, Johnsburg, Illinois, in which Brennan grew up. The pair had got together on the set of Francis Ford Coppola’s 1981 film “One from the Heart”, for which Waits was writing the music and Brennan editing the script, married a couple of months later at 1am at the 24-hour Always Forever Yours Wedding Chapel in Los Angeles.

The union liberated Waits from what may have appeared his inevitable fate: of the ultimate bar-room balladeer who descends into dissolution and obscurity. The singer had spent the first decade or so of his career toying with that possibility, living partly in the Tropicana motel on Sunset Boulevard, or in his car, a 1955 Buick, writing and singing about dereliction and doomed love, and playing up to a reputation for “wasted and wounded” chaos. For the first time, having met Brennan, he said: “I now believe in happy endings.” The experimentation of “Swordfishtrombones” was the first expression of that faith. “My life was getting more settled,” Waits recalled. “I was staying out of bars. But my work was becoming more scary.”

“Swordfishtrombones” (the title a winking tribute to Beefheart’s magnum opus, Trout Mask Replica) was a Waits-arranged pastiche, a variety of atmospheres from different sound planets. There is the warped, marching-army-ants music of “Underground,” an impressionist chant about people living below cities, but there was also the poignancy of the spare piano ballad, “Soldier’s Things,” the good bar yarn, “Frank’s Wild Years” (pre-figuring the musical of the same name), and the raggedy anthem to neighbourhood chaos, “In the Neighbourhood.” Yet the album was rejected by his long-standing record label, Asylum.

It was Brennan who gave Waits the courage to retire some of the seductive “piano has been drinking” myths of his own creation and to follow his restless musical intelligence, wherever it might take him. That album came out not long before the arrival of their first child. Two more albums (and two more children) followed in quick succession in the mid-1980s, “Rain Dogs” and “Franks Wild Years“. These are records of startling originality and playfulness, of cacophonous discord and sudden heart breaking melody, in which it seemed the artist was trying to incorporate the whole history of American song into his loose-limbed poetic storytelling.

To find the sounds he was looking for, the singer assembled around him a fearless collection of virtuoso musicians – the guitarists alone included Keith Richards and Marc Ribot. Waits once said in an interview, his band were required to do more than just keep up. “It’s like Charlemagne or one of those old guys said,” he noted. “You want soldiers who, when they get to a river after a long march, don’t start rooting for their canteen in their pack, but just dive right in.”

Waits was fresh off a 1982 Academy Award nomination for the “Tin Pan Alley”-style songs for Francis Ford Coppola’s “One From the Heart”. Island Records founder Chris Blackwell promptly signed him and released the album, the first Waits produced.

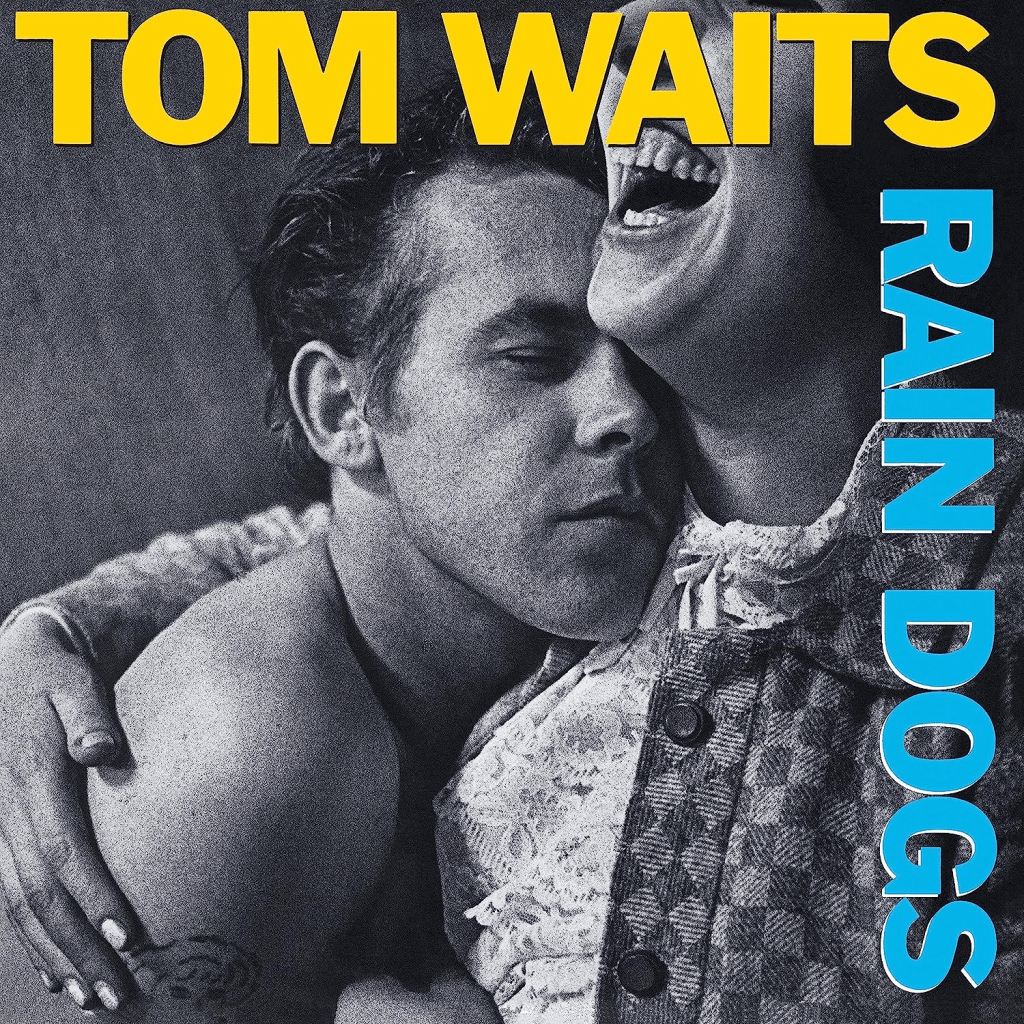

“Rain Dogs” came next Waits and Brennan moved to Lower Manhattan in 1984, when Brennan suggested it might be good for creativity. She was right. The 53-minute, 19-track album was a kind of mutant, late 20th century musical “Canterbury Tales” with a shape-shifting band. There were banjos and marimbas and bowed saw and parade drum and howling horns (and Keith Richards and Marc Ribot) on this rollicking, rough-hewn opus—and Waits was using his voice in increasingly weird-and-wild ways. The songs were stories, sagas, laments, breakdowns, character studies, comedies, cabaret numbers, and the moving anthem, “Downtown Train,” which was later covered by Patty Smyth and Rod Stewart.

For the second album of his trilogy, “Rain Dogs”, Waits and Brennan had moved from the west coast to New York, into a loft apartment in Little Spain, not far from Union Square, which Waits furnished with stuff he found on the streets. He was, he said at the time, completely overwhelmed with the immersive noise and talk of the city. “For the most part it’s like an aquarium,” he told one interviewer. “Words are everywhere. You look out of the window and there’s a thousand words.” That clamour of found poetry made its way into his songs, just as the skip-reclaimed furniture found its way into the apartment. He had a sense, he told David Letterman at the time, that living in lower Manhattan was like “being aboard a sinking ship. And the ocean is on fire.” That feeling ran through “Rain Dogs” (the name is a reference to the city’s rough sleepers, “people who sleep in doorways… who don’t have credit cards… who fly in this whole plane by the seat of their pants”).

Marc Ribot recalled last week the first day of recording. “We were in the old RCA Studios, which harkens back to a time when the labels owned studios,” he said. “This was a historic place, high ceilings, wood panels, a huge room, which could record an orchestra; we set up in a clump in the middle. There was a lot of amazing old equipment and amplifiers from something called the guitar society and a lot of unusual instruments.”

To loosen up his sound, Waits had mostly abandoned his go-to saxophone and double bass, filling the gap with all kinds of percussion and drums, marimbas and harmoniums and squeeze boxes. At the precise moment when music was becoming synthesised and digitised and sampled, he insisted on its traditions of heavy lifting. (“Anyone who has ever played a piano,” he liked to say, “would really like to hear how it sounds when dropped from a 12th-floor window.”)

He became interested in reviving the legacy of Harry Partch, who in the 30s and 40s had lived a hobo life in America, travelling in box cars, picking up ideas for instruments from junkyard materials, even creating his own form of notation. “I use things we hear around us all the time,” Waits said, “…dragging a chair across the floor, or hitting the side of a locker real hard with a two by four, a brake drum with a real imperfection, a police bullhorn… the problem is that most instruments are square and music is always round.” Keith Richards has recalled how when he arrived in the studio he thought: “Hello! He had a Mellotron… which was loaded entirely with train noises.”

“Tom spent the previous couple of years in New York, researching what a lot of downtown composers and avant-whatever musicians were doing,” Ribot recalls. “I think he was working with a really wide palette – but it wasn’t just to be weird. The key to Tom’s music is that he’s dealing not only with a lot of different music of the past, but with our memory of those musicians. We hear the music of the past on old scratchy records. He had this bass marimba because he was interested in a lot of Caribbean sounds, but specifically the way they sounded on 1920s and 1930s recordings rather than on today’s technology. He was interested in the whole history of folk and blues, but also a wider kind of Americana beyond that.”

Waits was writing through the night in an artist’s community building in Greenwich Village (he used to get home at 5am, just in time to feed his baby daughter). “There were tiny little rooms and each one had a piano in it,” he later recalled. “You could hear opera, you could hear jazz guys, you could hear hip-hop guys. And it all filtered through the wall.”

If the departure lounge for this new sound had been “Swordfishtrombones”, then the real disembarkation was its successor, “Rain Dogs”. That album opened with a sort of frenzy of dockside rhythm, press-ganging the band and the listener into places they might not have been before. “We sail tonight for Singapore,” Waits rumbled over the cacophony in his most guttural voice, and you didn’t for a moment doubt him. The voyage then took you to all manner of destinations.

Michael Blair, who later played with Lou Reed and Elvis Costello, provided percussion on the album. “For a multi-percussion player, it was like: pinch me, please. You know, how many times in your life would anyone ever get a chance to play with somebody who wrote so well, all these bulletproof songs, one after another. They could all really be pop songs, if you arranged them in a different way. Or if the singer had a different type of

Waits, he recalls, would never be specific about what he wanted; it would be “play like a Russian barmitzvah, or Alice in Wonderland”. “You didn’t say, ‘What does that mean, Tom?’ – you just went for it. I think when something began to sound like the song he wrote in his mind, that’s where we started.”

Ribot remembers how Waits would often be writing the lyrics moments before he sang them. “The groove was the main thing, which he would keep trying to communicate with the way he was moving his body and guitar.” As Richards recently said in an interview with Uncut: “[Tom] had a lot of rhythms going on in his head and in his body… the groove is another word for the grail. People search for it everywhere, and when you find it you hang on to it.”

“I think what a lot of people trying to sound like Tom Waits didn’t get,” Blair says, “is that for that ‘junkyard’ sound to work, you’ve got to first have a song that will stand up to having an axe taken to it.” Just when his tracks become most alarming, Waits would remind you of their haunting structure, like Picasso reminding you he could still draw like an old master if he wanted to.

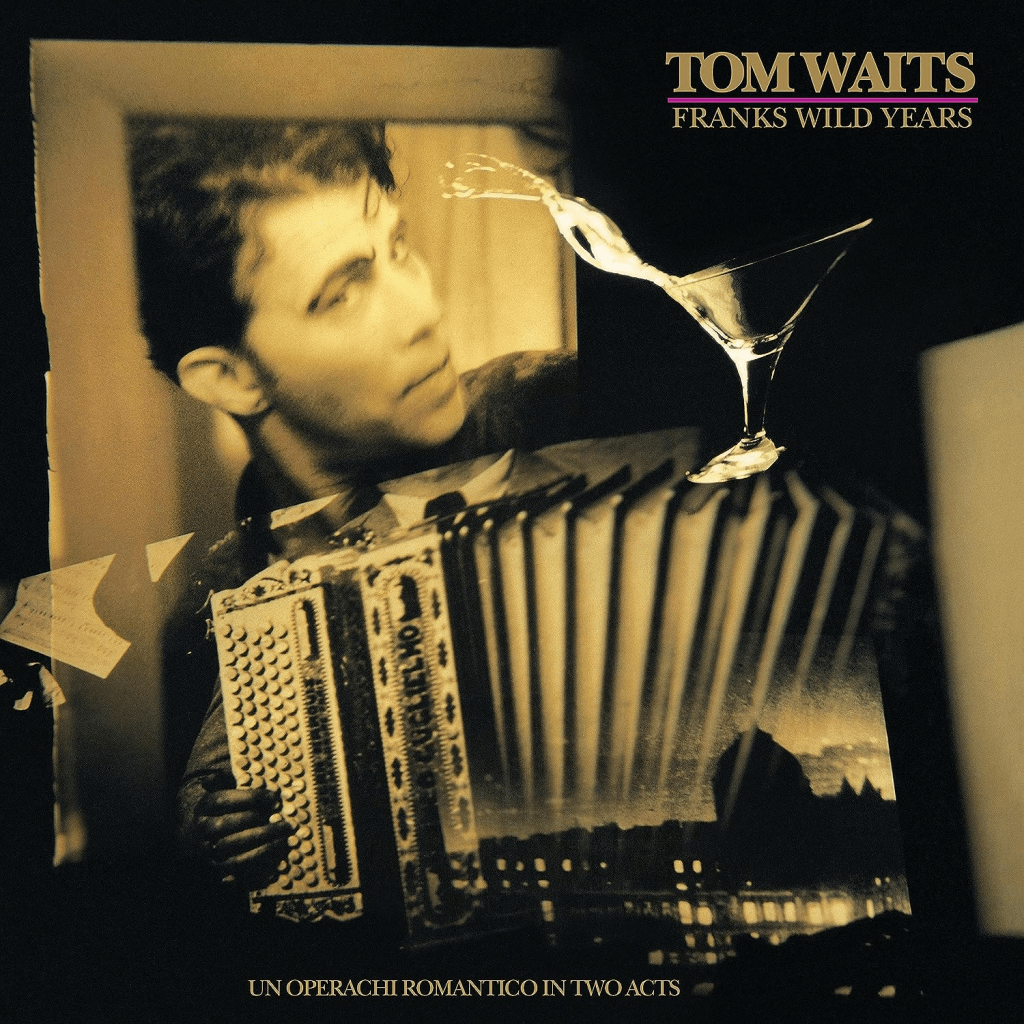

“Franks Wild Years”, the album, is based on the Waits musical of the same name, performed with Waits in the lead role by Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theater (directed by Gary Sinise) during the summer of 1986. Recorded mostly in Hollywood, the idea for “Franks” came from the “Swordfishtrombones” spoken-word piece in which a used-furniture salesman (Frank), suffocating in middle-class existence with a “spent piece of used jet trash” wife and her blind Chihuahua, Carlos, burns down his house. With smoking rubble in his rear-view mirror, he hits the freeway with the parting quip, “Never could stand that dog.”

Waits and Brennan developed this into Frank as an accordion player escaping the mythical town of Rainville for a calamitous but noble journey to Las Vegas and New York, in search of stardom. In the end, broke and bewildered, Frank—“a guy who stepped in every bucket on the road,” as Waits put it—dreams his way back to Rainville, while freezing on a park bench in St. Louis. Until he suddenly wakes up and finds himself home in the saloon where it all started.

“It closes a chapter, I guess,” Waits said when “Franks” was released. “Somehow the three albums seem to go together. Frank took off in “Swordfishtrombones“, had a good time in “Rain Dogs” and he’s all grown up in “Franks Wild Years.”

Waits’ vocal character varies wildly throughout the work’s 17 songs, and is no more impressive than when the gruff, growly singer turns to impeccable Sinatra-esque phrasing on the Vegas number, “Straight to the Top.”

Waits mythology has it that the original beat of the opening track of “Rain Dogs”, Singapore, was provided by Blair, the classically trained percussion maestro, whacking a cupboard with a hammer. Is that true?

Blair laughs. “It is actually. We had this sort of Kurt Weill accordion and oompah sound, and Tom wanted to give a sense that the world is going to fall apart. We had a look around the studio, in the kitchen and the bathroom, wondering what might give that sound, of someone trying to break the door down. There was an old dresser in one of the storage rooms. All the way through it’s me with a real hammer bashing it. We could have sampled it, I suppose, but it would not have been the same.”

The New York Times named “Rain Dogs” the best album of 1985, and though sales in America were slow, Waits was beginning to find a new audience in Europe. The subsequent tour – which like all of Waits’s sporadic tours ever since have been the hottest ticket in any city – proved that he was sailing in the right direction.

Waits once recalled to the journalist Barney Hoskyns how, before he made “Swordfishtrombones”, he had a terrible nightmare. He was in a Salvation Army store and flipping through a stack of old vinyl records when he came upon one of his early singer-songwriter efforts. “The sleeve,” Hoskyns related, “stared at him reproachfully and he knew something had to change. He had to create something unique, ‘something you’d want to keep’.” Forty years on, still married to Brennan, living somewhat reclusively on a smallholding farm where they write and create together – “I wash, and she dries” is how he describes it – he is seeing that ambition come true.

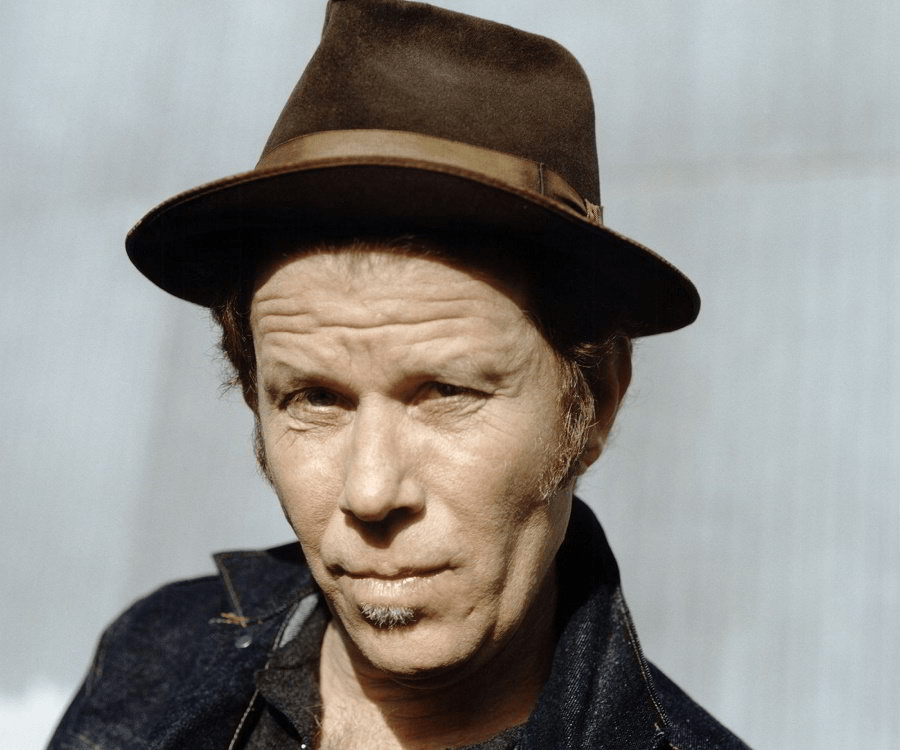

All albums were mastered by Chris Bellman at Bernie Grundman Mastering under the guidance of Waits’ long time audio engineer, Karl Derfler. The new vinyl editions will come with specially made labels featuring photos of Waits from each era in addition to artwork and packaging that has been painstakingly recreated to replicate the original LPs, which have been out of print since their initial release.