Formed in 1963, and part of the first wave of the British blues boom, the Groundhogs initially came to public attention as John Lee Hooker’s backing band when the veteran bluesman paid a visit to the UK in 1964. More gigs followed with Jimmy Reed and Champion Jack Dupree, and in 1968 they were signed to Liberty Records by future Wombles supremo Mike Batt. However, it wasn’t long before the band were embracing the new progressive aesthetic with their 1969 album, “Blues Obituary”, proclaiming in no uncertain terms a move away from blues purism towards pursuing a more experimental direction.

The Groundhogs were also one of the coterie of underground bands on the Liberty/United Artists roster, which included Hawkwind, Man, Can and Amon Düül II. The four albums they recorded between 1970 and 1972 – “Thank Christ For The Bomb”, “Split”, “Who Will Save The World?” and “Hogwash” – saw the band become increasingly ambitious, both compositionally and conceptually, with the deployment of Mellotron and synth helping to create an exciting progressive/blues rock hybrid.

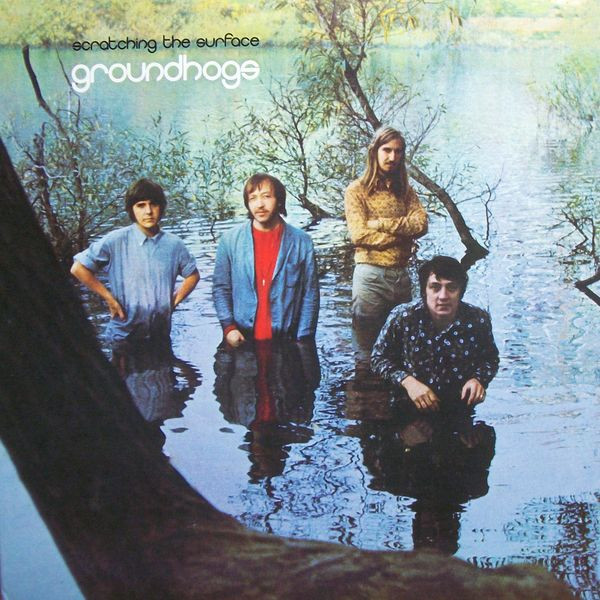

“Scratching the Surface” (December 1968)

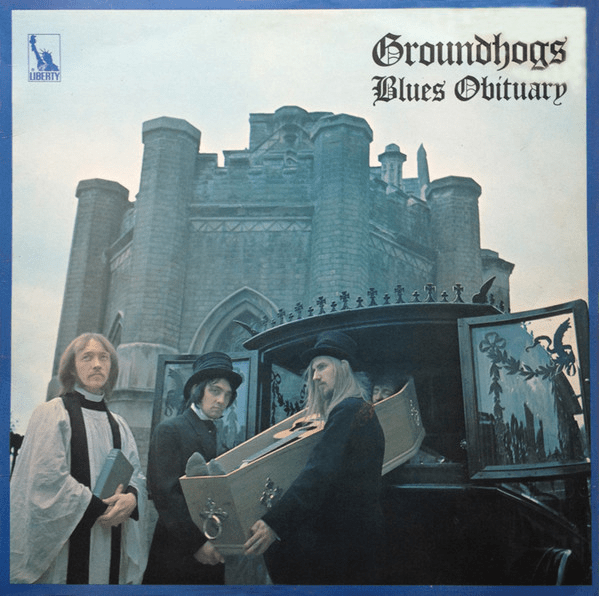

“Blues Obituary” (September 1969)

The second blues boom in Britain was short-lived, and in order to keep the Groundhogs working McPhee decided to transform the blueprint. To follow-up their Mike Batt-produced debut, “Blues Obituary” was recorded in June 1969 at Marquee Studios in London with Gery Collins and Colin Caldwell engineering, the rote 12-bar sound transformed into something hypnotic, underground, supercharged. McPhee’s guitar is a thing of descending drones and howling shamanic dread, his vocals of paranoia and disaffection made eerie by his ability to bend words like notes, à la Son House. In case the message was unclear, the cover, shot in Highgate cemetery, left no one in doubt.

By the time of 1969’s “Blues Obituary”, McPhee had absorbed the influence of Jimi Hendrix, acknowledged the death of 12-bar blues “authenticity” and embraced the power of amplification and studio production. Operating as a power trio of McPhee, bassist Pete Cruickshank and drummer Ken Pustelnik, the band were determined to make a statement with their next album: “The idea of the title came from a discussion with Roy Fisher, Groundhogs’ manager at the time. John Lennon had said that The Beatles were bigger than Jesus and got a lot of publicity, so we were trying to think of something that was as contentious as that. Roy said, ‘Thank Christ for the bomb’, and it all clicked in my head.”

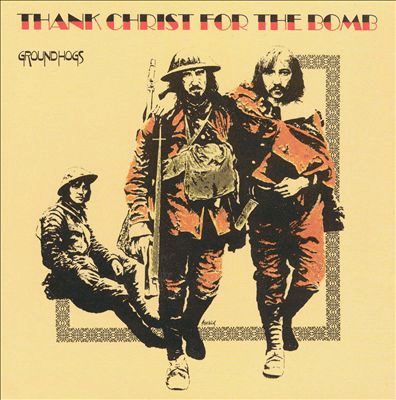

‘Thank Christ for the bomb’ (May 1970)

It’s hard to figure what happened to McPhee in the months between ‘Blues Obituary’s” release and the 1970 sessions for “Thank Christ for the Bomb” Whatever the impetus, the latter album represented an enormous progression. ‘Thank Christ’ is a startling statement so different from the previous Groundhogs records that it might as well have been made by a different band. McPhee, Cruickshank, and Pustelnik left the blues behind for a batch of songs that link the after-effects of the psychedelic era to the first flickers of the prog rock period, with plenty of hard-rock roar and some of the most explosive, expressive guitar solos ever committed to tape.

McPhee had set about writing a set of songs full of contrasting riffs and chords – still recognisably blues rock, but skewed into dynamic new shapes. The lyrics were also a major advance from traditional rock’n’roll platitudes; the first side of the album is based around the theme of alienation, while the second tells the story of a rich man who renounces his status and embraces poverty instead. Soldier deftly portrays the brutalising effects of war, set to an irresistibly catchy riff: “We really got our boost when John Peel played “Soldier” on his programme, he liked the song and the lyrical complexity.”

McPhee made a supercharged power-trio concept album, a crunching mix of Sabbath, Beefheart, and the trio’s brand of harmonic heaviosity, as side one ruminates on two World Wars and the bomb culture generation, and side two tells of a Chelsea gentleman who returns to nature, “my food from bins, my water from ponds”.

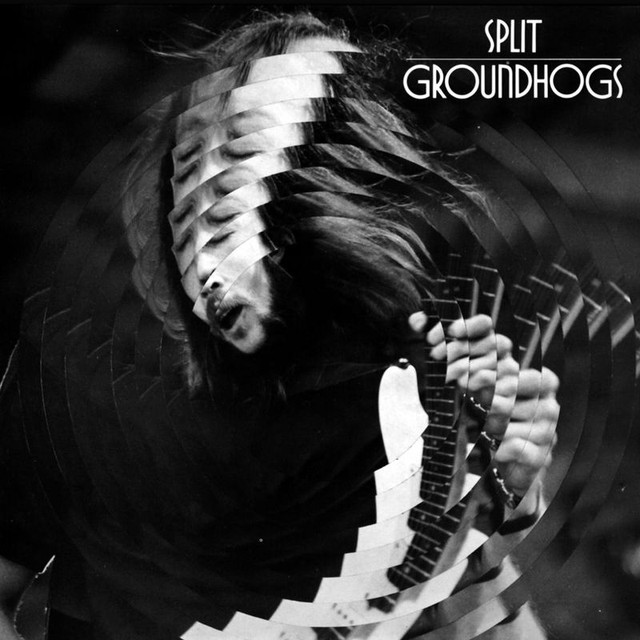

“Split” (March 1971)

Building on their popularity as an explosive live act, and coming off the back of opening for the Rolling Stones on their 1971 UK tour, “Split” was the Groundhogs’ most successful album, peaking at No.5 in the UK charts. Another set of spiky, twisting songs, it includes their most well-known track, the punk blues stomp of “Cherry Red” (from where the record label takes its name), which, despite not being released as a single, even secured them a slot on Top Of The Pops. But McPhee had higher aspirations in mind.

Occupying the first half of the album is a four-part suite inspired by a very real mental breakdown McPhee had experienced. It brilliantly rides the line between derangement and control, with McPhee’s mad, magical guitar work more jaw-dropping than ever. It’s an instrumental and lyrical expression of schizophrenia, a frantic scouring storm of discordant sustain, fuzz and wah wah guitar patterns, thunderous drumming, earthquake bass, and addictive riffs incorporating ideas of split personalities, loneliness, and Yogic mind and body separation. With a second side that features the scorching, pummelling euphoria of “Cherry Red”, the psychedelic Black Sabbath dirge A Year In The Life, and Groundhog, McPhee’s rearrangement of “Ground Hog Blues“, the John Lee Hooker song that gave the band its name, the album became an immediate best seller

“Thank Christ For The Bomb” got to No.9 in the UK charts, and significantly raised the Groundhogs’ profile. They also started playing alongside many of the emerging prog bands, including Yes, Curved Air, Gentle Giant and Colosseum, although McPhee admits: “I wasn’t enamoured by some of the bands in the progressive scene at that time – I didn’t like the soft, fluffy sound that they produced.” Instead, he drew inspiration from the darker, edgier sounds of groups such as King Crimson.

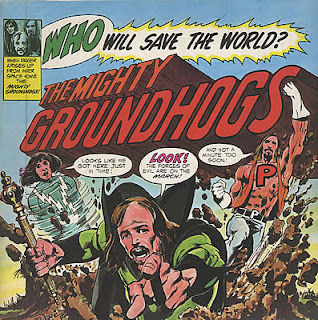

“Who Will Save The World?” (March 1972)

“Who Will Save The World?” is where the band’s prog inclinations really start to become apparent – just listen to the jazzy riffs and dramatic Mellotron of “Earth Is Not Room Enough” and “Music Is The Food Of Thought”. It’s another loosely conceptual album, addressing the various evils threatening the world – overpopulation, war, big business… But its presentation was anything but po-faced, with DC and Marvel Comics’ artist Neal Adams brought in to create a fold-down comic strip sleeve, with the band reimagined as superheroes The Mighty Groundhogs. “I was a big fan of Silver Surfer, as drawn by Neal,” says McPhee. “Once I saw the artwork he’d come up with, I wanted to write all the songs to link with it.”

However, despite getting to No.8 in the UK charts, it got a decidedly frosty reception compared to their previous albums. “A lot of fans and the press didn’t like it. To be honest, it was rushed and I never had the time to work on the production or even think about what we were playing, and I agreed with them for a while. It was only a few years later, when I could listen to it objectively that I realised its strengths. We often get people now saying that it’s their favourite album.”

Undaunted, McPhee continued to take the band in a more progressive direction, adding an ARP 2600 synthesiser to their musical armoury. And following the departure of Pustelnik, the band’s new drummer was none other than Clive Brooks from Canterbury scene stalwarts Egg, who had supported the Groundhogs on tour. “Clive was a lovely man and there was a lot less stress involved with getting together on time playing and touring,” says McPhee. “He was a powerful player who suited the times and new material that I was writing.”

“Hogwash” (November 1972)

Alas, the public weren’t receptive to McPhee’s increasingly outré take on blues rock, and “Hogwash” failed to chart. It also proved to be their last album for United Artists, with the band signing to WWA, the short-lived label set up by Black Sabbath’s management team. They released the album “Solid” in 1974 – which, as the name suggests, was a retreat from the more expansive sound of “Hogwash” – before splitting up for the first time the following year.

That new material would emerge on the brilliant “Hogwash”, the band’s most overtly progressive album. Not only are Mellotron and synth more to the fore than ever, in particular on the tracks “You Had A Lesson” and “Earth Shanty”, but the clever arrangements and segues between songs make for a genuinely sophisticated and powerful listening experience. McPhee’s lyrics are also some of his most challenging. For instance, opener “I Love Miss Ogyny” is a chilling depiction of domestic abuse from the point of view of the abuser, the song’s stop-start dynamic reflecting its dysfunctional theme.

Placed behind their predecessors but they were still head and shoulders above what most bands were doing at the time. And in between those two records, McPhee took time out for a 1973 solo album that featured his furthest-out expedition ever.

“Solid” (June 1974)

As suggested by its perfunctory, artless cover image – McPhee, Cruickshank and drummer Clive Brooks, who had replaced Ken Pustelnik two years earlier, gloomily stare – “Solid” is a cold, sterile, angular work, at times closer to post-punk than prog-blues. Right from the sickly, phased, multitracked guitars and brute-rhythm section of the album’s opening track “Light My Light” (lyrics about death, decay and a darkened Earth) we are in a fug of existential and environmental despair. Riffs stab, keyboards jab, vocals bite and the LP is drenched in a trebly metallic sweat of high anxiety and fear. Managing to alienate band, record company and management, it arguably signalled the end of the group as a true creative force.

Yet before that had come the apogee of McPhee’s experimental impulses, with the release in 1973 of his first solo album, “The Two Sides Of Tony (T.S.) McPhee”. On one side was a collection of folk blues numbers, and on the other an avant-garde electronic symphony entitled “The Hunt”, performed on the ARP 2600 and a Rhythm Ace drum machine, which still sounds completely out there today. “I’d been using the ARP 2600 during gigs for the “Hogwash” tour and wanted to explore its potential. It also gave me an opportunity to express my loathing for people who hunt foxes. I stand by what I said then, there are still a lot of arrogant people who get a kick out of cruelty.”

The Groundhogs may have existed on the periphery of the prog world, but the way it informed their music in the early 70s is a fascinating example of cultural cross-fertilisation. And while they perhaps never quite made it into rock’s premier league, they released some of the era’s most innovative and exciting albums, and retain a devoted fanbase to this day,

“Crosscut Saw” (February 1976)

Originally intended as a Tony McPhee solo long-player before management encouraged the guitarist to release it under the Groundhogs name, this low-slung affair of slow, loping menace finds McPhee’s guitar corrupted and perverted by the EMS Synthi Hi-FLi guitar effects unit, his mind turned bitter by divorce. Visceral lyrics of paranoia and recrimination are spat out over epic space-blues dirges that shift jarringly into analogue storms of sci-fi disturbance and frenzied metallic trauma. Vastly underrated, and deeply unsettling, it’s an album that ultimately feels closer to schizoid Sabotage-era Black Sabbath than the Groundhogs of two years earlier.

“Our music is often so basic people miss the point,” said McPhee. “On live gigs we’re never the same twice – one night they might think it’s Captain Beefheart up there and the next Muddy Waters. It should be a spontaneous reflection of the musicians’ emotions on the night.” Such statements were often McPhee’s way of defending the fact that the Groundhogs could be an erratic live band who struggled to replicate their studio-augmented power on-stage. Taken from three outside broadcasts between 1972 and 1974, this is almost certainly their finest live document, containing the best-ever live renditions of “Split Pt.1” and “Cherry Red”.

Despite uniformly cringe-inducing album covers that would have made even Spinal Tap recoil, The Groundhogs’ late ’70s-’80s albums are actually quite solid, but different from what came before. While it’s true that most of the quirkier elements of the band’s sound had been sanded off in favour of a more straightforward approach, and it must be admitted that the lyrics began taking a bit of a nosedive, sometimes descending into rock ‘n’ roll cliché, McPhee’s artistry remained so strong that the records work on their own terms, even if they’re far from the triumphs of the band’s early days.

The Groundhogs could have been bigger stars on the homefront in their heyday. And they should have made more of a mark in America, where their discography was strictly the domain of the kind of music geeks who obsessively haunted the import bins. But with the dazzlingly gifted Tony McPhee at the helm, they crafted some of the most arresting records of their era,