On May 27th, 1968, Iron Butterfly recorded their classic song “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida”. Iron Butterfly’s signature track and often considered one of the most influential songs on the heavy metal movement — especially in the United States. A progressive rock gem, as well, “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida” has also been known for its length. Perhaps the highlight of the track is Ron Bushy’s drum solo at just over the six-minute mark. It delivers a kind of Jungle vibe. It builds up to a frenetic pace and cools off before the band comes together for a collective jam. Bushy again moves into the forefront at the 13-minute mark; an overall drum performance that was quite impressive for the late 1960s, and helped define this epic rock classic.

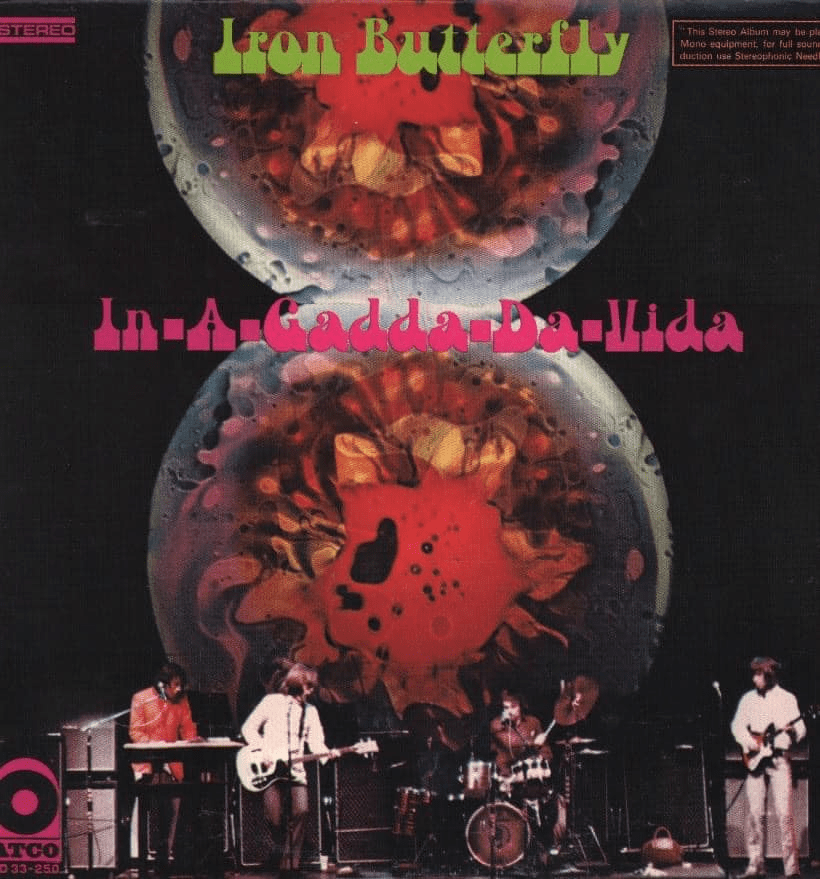

Okay – anyone who wants to make fun of hippie-era silliness has all the fuel they need in this album’s title, also that of the group’s #30 hit song of the same name (a just under three-minute edit of the 17-minute album track). The band’s stature as hard rock progenitors is underscored by the title of their previous album, “Heavy“, and big worldwide sales of “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida” certainly helped spread the sound.

At slightly over 17 minutes long, it occupies the entire second side of the “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida” album. The lyrics are simple, and heard only at the beginning and the end. The track was recorded at Ultrasonic Studios in Hempstead, Long Island, New York. The original title of the song was “In The Garden of Eden”.

The recording that is heard on the album was meant to be a soundcheck for engineer Don Casale while the band waited for the arrival of producer Jim Hilton. However, Casale had rolled a recording tape, and when the rehearsal was completed it was agreed that the performance was of sufficient quality that another take was not needed. Hilton later remixed the recording at Gold Star Studios in Los Angeles.

In later years, band members claimed that the track was produced by Long Island producer Shadow Morton, who earlier had supervised the recordings of the band Vanilla Fudge. Morton subsequently stated in several interviews that he had agreed to do so at the behest of Atlantic Records chief Ahmet Ertegun, but said he was drinking heavily at the time and that his actual oversight of the recording was minimal. Neither Casale nor Morton receives credit on the album, while Hilton was credited as both its sound engineer and producer.